There are certain, not ideas, but idea-shaped impressions that long outlive their expiration date, being useful to those who possess the appetite but not the enterprise to develop a philosophy of their own. One of the most prominent and persistent of these over the past 30 years is the purported clash of civilizations between the Muslim world and the West, two undefinable regions that act as screens upon which countless often self-contradictory fantasies may be projected. Another is the cuddlier but no less stupid proposition that degeneracy and malice are forgivable or at least immune from criticism if they can be justified in the name of “cultural difference” or deemed the consequence of some historical injustice.

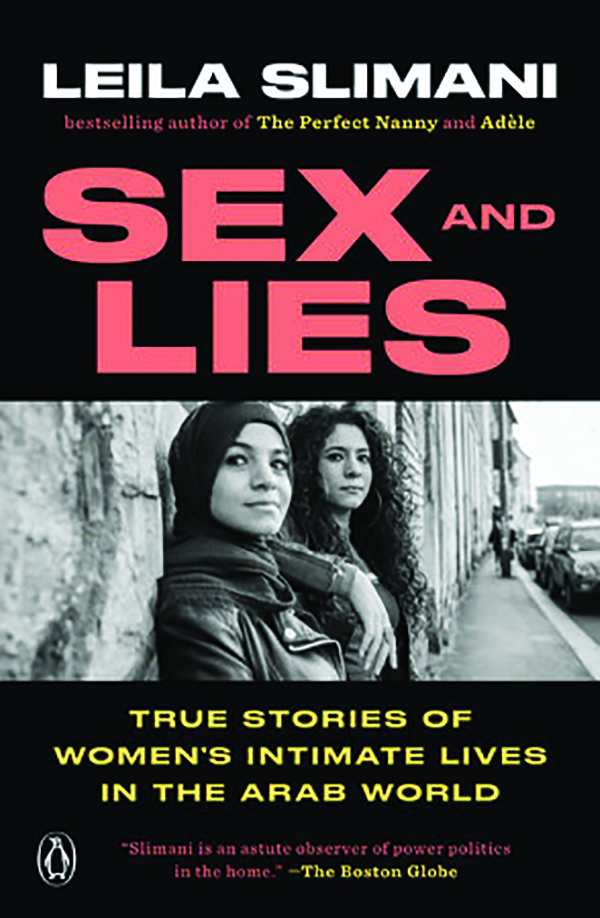

With debates around Islam so frequently cast in such vehement, useless terms, one must be grateful to Leila Slimani, a writer who has avoided the temptation to overlook the shortcomings of her native Morocco and its official religion while refusing to become a professional apostate. In an anthology of essays on the Islamic State, she proclaimed, “Sharia makes me vomit,” but her novels are withering in their portrayal of the emptiness of middle-class life in a spiritually destitute France. In 2017’s Sex and Lies, newly published in English, she writes about sexual codes and practices in the land of her birth, where abortion, prostitution, homosexuality, and extramarital sex are outlawed and those who practice them often thrown in prison.

The book originated in a two-week tour around Morocco to promote her first novel, Adele, the tale of a well-off woman with an outwardly perfect life who escapes monotony through a series of impersonal, frequently brutal sexual encounters. After her readings, women approached her, wanting to discuss their own sex lives. Slimani records their stories, interspersing them with remarks that give political or historical context. Her purpose isn’t sociological, and for broader insights, she refers to other experts in the field, including esteemed feminist Fatema Mernissi, to whose memory the book is dedicated. Instead, she presents these women’s stories as signs of their vitality, a respite from their isolation, and proof of complexities and conflicts that fundamentalists and their critics are more comfortable denying.

Slimani speaks with affluent professionals, housewives, a prostitute, and a girl inspired to produce the play The Vagina Monologues in Rabat. Though most of her interviewees are women, she also talks to a policeman who makes no secret of the hollowness of the policies he enforces: “There’s no morality in it, no faith: It’s the law of cash. The law of what speaks loudest.” The predominant themes of the women’s confessions are a virtual absence of sexual freedom, a perverse fixation on female virginity and on women as a sexual possession, and a “morbid puritanism” that prevents women from socializing at ease because they might stray from their own marriage or prove too mighty a temptation for another woman’s husband.

Everyone Slimani speaks with denounces Morocco’s hypocrisy. Many remark on the country’s rampant prostitution and pornography consumption and the frequency of illegal abortions. For Slimani, this is a class issue. As the tribute vice pays to virtue, hypocrisy is profoundly regressive: “It’s the poorest, the most vulnerable, and the women in particular who pay the greatest price for this sexual repression, while the well-off are able to live their sex lives more or less as they wish.” Moreover, she suggests that the unwillingness to talk about sex or the sense that sexual transgressions are permissible so long as they are kept secret accustoms Moroccan citizens to duplicity, allowing corruption to propagate in other areas of society.

A brash 28-year-old, after telling Slimani the tale of her own rape and of the promiscuity of her fellow students at university, says revealingly, “I think the problem is not that we’re conservative but that we’re f—ed up. Love and affection are as taboo as sex.” Slimani has devoted a book to French-Jewish philosopher Simone Weil, who wrote movingly about the essential place of love in coming to know one another, and a deeper attention to her ideas might have been welcome here; at any rate, it is intriguing, if deeply sad, to see how this absence of love makes itself felt in these women’s lives. In the best cases, they have to sneak around, lead double lives, and curb whatever urges are seen as indecent. At worst, they face outright hatred, violence, manipulation, even forced marriages to “emotional parvenus” for whom a woman is no more than an instrument for pleasuring themselves.

For a broader view of where Morocco stands, Slimani consults sociologist Abdessamad Dialmy, whose work has covered every aspect of sexuality in Morocco from human trafficking to the prevalence of condom use. For him, the country’s attitudes must be viewed in light of a transformation of mores any number of countries has undergone:

If this is true, then there are reasons for guarded optimism. In the wake of the outcry surrounding the suicide of 16-year-old Amina El Filali, forced by her family to marry a man who raped her, Morocco finally revoked Article 475 of its penal code, which exonerated rapists who subsequently married their victims. Morocco has committed to eliminating child marriage and forced marriage by 2030. Much remains to be done, but “democracy is a long road,” in the words of the Spanish novelist Juan Goytisolo, who recalled that Western countries needed centuries to abandon despotism in favor of individual rights and representative government.

Slimani and her informants make a compelling argument that sexuality is not trivial to individual freedom, that “sexual rights are a part of human rights,” and that sexual repression, far from a minor infringement, is a fundamental aspect of tyranny. It is heartening that she does so with an appeal to Enlightenment values at a moment when more and more liberals seem contemptuous of the very belief that people can understand each other, preferring to parcel them up into various categories of the privileged and oppressed that determine their right to speak or else their duty to be silent. In an interview with Elle, Slimani declared, “I defend the universality of sentiments and bodies.” The universalization of rights demands a common basis of understanding, a sense of the basic way in which you and I are alike and thus have equal moral claims, and, putting aside the bare requirements of nourishment and lodging, I am not sure there is a better right than the need to love and be loved.

Adrian Nathan West is a literary translator, critic, and the author of The Aesthetics of Degradation.