The best American art is often hidden. Sometimes, it conceals itself in pop culture, hiding in plain sight by disguising itself as a commercial product. Think muscle cars, comic books, or the middle seasons of It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia. In these instances, high art dons blue jeans and a T-shirt and mingles with the proles. More often, though, the best American art, and particularly literature, dies from underexposure. Without insinuating itself into a market, there simply isn’t an audience for it. Such was the case with Moby Dick until it was resurrected by D.H. Lawrence in the 1920s. Who knows how many masterpieces have yellowed into dust, unloved and unread, while the cultural machinery of the republic fed off the basest drives of the lowest common denominator?

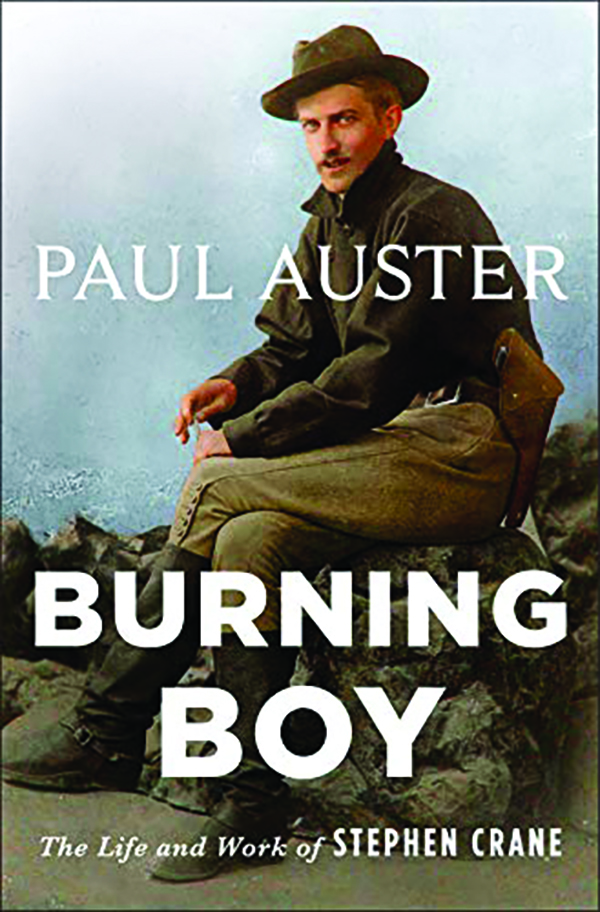

The writing of Stephen Crane has the somewhat cumbersome fate of being hidden in both senses. He enjoyed massive commercial success at the end of the 19th century with exciting, often prurient works such as Maggie: A Girl of the Streets and The Red Badge of Courage. As celebrated novelist Paul Auster writes in his lush and fascinating new biography, Burning Boy: The Life and Work of Stephen Crane, “Once upon a time, almost every high school student in America was required to read The Red Badge of Courage.”

But Crane’s fortunes have changed. “Now,” writes Auster, “for reasons I find difficult to understand, the book seems to have fallen off the required reading lists.” Just as disturbing for Auster, none of his non-English-speaking literary acquaintances had ever heard of Crane, despite his work once being internationally acclaimed. Crane and his work, Auster tells us, “which shunned the traditions of nearly everything that had come before him, [and] was so radical for its time that he can be regarded now as the first American modernist, the man most responsible for changing the way we see the world through the lens of the written word,” has died a second death. Only a handful of specialists remain to pick over his corpse.

Auster has written a strange, wonderful book, full of contradictions. Like Auster’s fiction, Burning Boy is vast and almost hypnotic in its length — a curious tribute to a man who lived a brief, action-packed life and died before the age of 30. But it’s obviously a product of passion. Every page glows with Auster’s admiration for his subject. Auster wants us to love Crane as he loves Crane, and so the language of Burning Boy has all of the heavy, obsessive energy of a stalker’s manifesto. That’s a good thing. Stalker energy is interesting when the object of fascination is long dead. But what it means is that we get almost as much Auster as we do Crane. This can be occasionally annoying, as when Auster acts nebbishly befuddled by Crane’s love of hunting, which reveals more about Auster than Crane or hunting, but for the most part, Auster’s love of a writer he ranks alongside “Twain, Poe, Hawthorne, Emerson, Whitman, and Henry James” is infectious.

Burning Boy is an ambitious project. In it, Auster sets out to accomplish three things: to tell us about Crane’s life, to tell us about Crane’s work, and to tell us about Auster’s reactions to both. Although Crane died at 28, probably due to complications from tuberculosis and a malarial fever he had picked up in Cuba, relating the circumstances of his adventurous life is a bigger task than one might guess. “It was a weird and singular life,” Auster tells us. Born in Newark to devout Methodist parents, Crane was a precocious youth who started smoking when he was 6 and seemed more interested in playing baseball than in attending the various colleges he dropped out of. He was a self-taught writer whose satirical description of a union parade in Asbury Park “disrupted the course of the 1892 presidential campaign.” As a journalist, he went toe-to-toe with the NYPD in a corruption battle that “effectively exiled him from the city” in 1896, was shipwrecked off the coast of Florida, had a common-law marriage to the proprietress of a “bawdy house,” was a war correspondent on the front lines of the Spanish-American War, and was friends with such eminent writers as Joseph Conrad and Henry James, the latter of whom is said to have “wept over” Crane’s early death. Crane certainly burned, fast and brightly.

These events wouldn’t mean all that much to us if the man of action hadn’t also been one of the best American prose stylists to put ink on paper. Auster, himself a master novelist, puts the bellows to Crane’s fiction, reigniting embers that have grown cold from neglect. Auster’s bit about Crane’s still-shocking novella Maggie: A Girl of the Streets, published in 1893, is particularly stunning. The basic plot is simple enough: a good-hearted girl struggles to survive amid the violence, poverty, and degradation of turn-of-the-century New York City. But Auster walks us through the work, chapter by chapter, and teases out the shocking originality of its construction in language that is equally thrumming with life. Savage violence is related in language that is simultaneously inflated and anodyne, language that merges “into an authorial stance of ironic detachment, the same distancing effect to be found in the early stories of Joyce and Hemingway, the novels of Camus, and the work of countless other writers of the next century.” Auster goes on to write:

Crane was the first to establish that tone. He surveys the carnage wrought by his characters with the steady eye of a war correspondent, turning a potentially hysterical, out-of-control scene into a starkly delineated portrait of human actions, and because he doesn’t flinch at any point in the nineteen chapters of the narrative, his book breaks new ground, departing from both the plodding, exhaustive naturalism of Zola and the mild-mannered realism of [William Dean] Howells to establish a literature of pure telling, with no social analysis, no calls for reform, and no psychological reflection to explain why the characters do what they do. They simply act, and Crane tells. For the first time in American fiction, the reader is not told what to think — only to experience what happens in the book and then to draw his or her own conclusions.

After reading that passage, is it still a mystery why Crane, the progenitor of what would become literary modernism, has been dropped from required reading lists? Auster’s book is a triumph, as they say, but not only for the reasons he intended. Yes, it’s a wonderfully written biography of Crane. It explores his work with almost reverential patience. But the project itself suggests the shortcomings of today’s literary culture. It is really a monoculture, one dominated by overeducated and underlived folks who use literature as a vessel to convey their two-dimensional didacticism. None burn as bright as Crane. Those who do are mostly hidden, concealed tombs waiting to be unearthed by future archaeologists of American culture.

Scott Beauchamp is an editor for Landmarks, the journal of the Simone Weil Center for Political Philosophy. His most recent book is Did You Kill Anyone?