Poor Lionel Essrog can’t get any rest. The protagonist of Jonathan Lethem’s fifth novel, Motherless Brooklyn, is a would-be private detective with a bad case of Tourette syndrome. Ordinary interactions send Lionel off on rude streams of consciousness and eruptions of echolalia that shatter the quiet on stakeouts, put cops and dames on edge, and make it hard to have a moment’s peace.

But as Lionel alone seems to understand, Tourette’s also gives him a kind of superpower as a detective: a mind so compulsive and restless it’s incapable of leaving any rock unturned. “Tourette’s teaches you what people will ignore and forget,” Lionel narrates early in the book, ”teaches you to see the reality knitting mechanism people employ to tuck away the intolerable, the incongruous, the disruptive — it teaches you this because you’re the one lobbing the intolerable, incongruous, and disruptive their way.”

Besides, there’s no time to rest. The novel opens with the murder of Lionel’s mentor, Frank Minna, who owned the small-time detective agency where he works, and it’s a race from there to find the killer. Also working the case are the other former orphans who Lionel grew up with and who Minna rescued from the St. Vincent’s Home for Boys and groomed to work for him. Fatherless twice over, Lionel knows that ultimately it’s up to him, the freak show gumshoe, to make sense of it all.

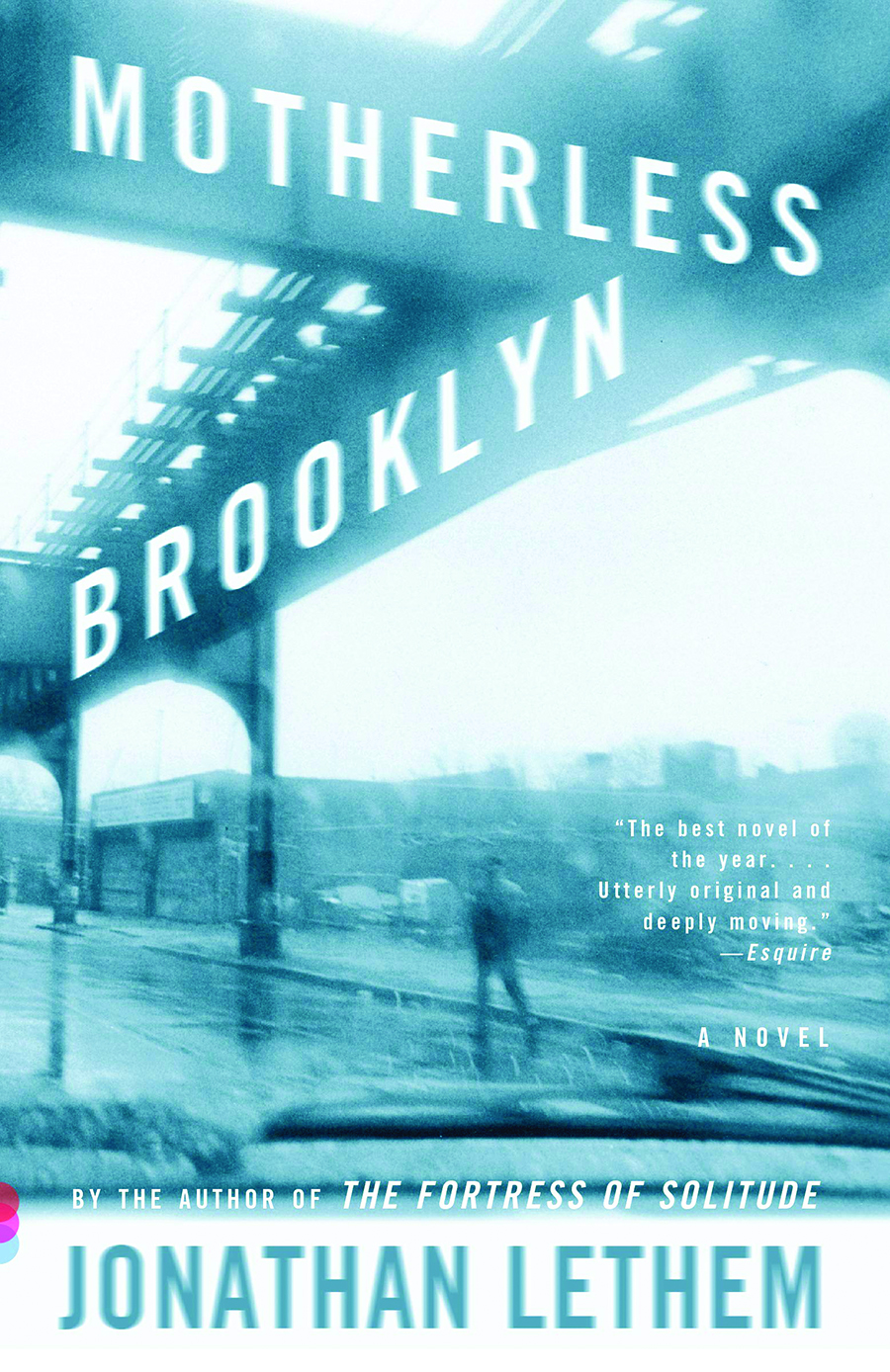

Published in 1999, Motherless Brooklyn is not Lethem’s masterpiece. That would be his next book, 2003’s The Fortress of Solitude. It was, however, the culmination of a style, the shaggy genre novel, that Lethem had been perfecting since his debut book, Gun, with Occasional Music (1994), first blended Philip K. Dick’s amphetamine dialogue and science-fiction gnosticism with the structure of hard-boiled detective novels, the metafictional framing of Don Delillo, and the wiseacre irony of Devo and stoned comic book aficionados.

In his early work, Lethem hadn’t been trying to write the great American novel. He had followed the genre and outsider fiction path instead, drawn there by a love of the stories and style, the weirdness and possibilities offered by the form. Freed from the obligations of high literature yet forced to entertain, genre fiction allows writers to experiment within the tightly bound conventions of a story that actually has to pay off for readers. Motherless Brooklyn, a novel about a Tourettic detective with an affinity for Daffy Duck investigating a murder tied to a Zen monastery, accepted the risk of being ridiculous and achieved unruly greatness.

Tourette syndrome is an isolating condition. It traps Lionel inside of his mental tics — when he first meets Minna, he can’t stop tapping him on the shoulder — and forces him to translate his own botched language to have any chance at all of being understood. But while it isolates him from other people, it connects him to New York City itself. The great discovery of Lethem’s novel is that New York has Tourette syndrome, too. What is the city but a buzzing, hissing riot of unscratchable itches, rumbling through the subway system and surfacing in the skittering tap-tap-tap rhythm of conversation that bounces through the streets?

For two decades, the actor Edward Norton has been laboring on a film adaptation of Motherless Brooklyn. A book whose protagonist can’t help but belch out words is self-evidently one written in the Joycean spirit of sound poetry and love of language. And there’s a reason why so few films have been made of Joyce novels: logorrheic prose play doesn’t translate to the screen. But genre novels do, which makes the dreary ineptness of the film released last month all the more disappointing.

Much has been made of Norton’s decision to move the story back in time and set it in the 1950s instead of the ‘90s, a choice he made because he worried that putting the snappy noirish dialogue in a modern setting would have drawn too much attention to itself. But setting the film in the ’50s and shooting it in a sedate greenish-blue tint doesn’t make the story feel more natural, it just gives it the staged quality of a period piece. With the weird incongruities and disorienting landscapes of the novel flattened out, the film is left to succeed or fail as a conventional noir.

The problem is that Norton doesn’t seem interested in genre art. Rule No. 1 is that the plot is just there to give the characters something to struggle with and talk about. The plot can’t actually matter, since the whole point is to watch unfold, over and over again, among the rich and poor alike, the same classic tragedy of weakness and temptation leading to the fall.

What the great detectives all know is that everyone’s guilty of something. Solving the mystery of a crime is just about putting the pieces in the right order, which is why Norton’s decision to replace Lethem’s absurd and byzantine plot about Zen monasteries and New England sea urchin farms with a thinly veiled allegory about Robert Moses, the archvillain of New York City development lore, is not only an artistic failure but a kind of embarrassing misunderstanding.

The movie does feature some nice acting, especially in scenes with Willem Dafoe as the spurned brother of the Moses character, played by Alec Baldwin. But even Baldwin, who’s shown a talent in the past for playing stock characters in interesting ways, falls flat here. “Do you have the first inkling how power works?” Baldwin’s Moses, wearing a bathrobe, ask Norton’s Lionel, toward the end of the film. “Power is knowing that you can do whatever you want and not one person can stop you.” Baldwin’s character is a rapist, in case the dialogue doesn’t carry the point, but the effect is hokey instead of menacing, a naive moralist’s idea of a sociopathic power broker.

It’s very easy to imagine how Lethem’s novel might have wound up as a bad joke in the hands of a lesser writer. Three hundred pages of narration by a Tourettic private eye fixated on Prince and the ideal form of the Brooklyn bodega sandwich (the secret is to preserve the pockets of air between the slices of deli meat) could quickly wear thin. Lethem avoids this through his supremely inventive prose, improvising his way out of repetitiveness even while riffing on the theme of compulsive repetition. More importantly, he’s willing to be the butt of the joke. Rather than straining over Lionel’s wackiness in a way that forces the reader to acknowledge the author’s big brain, he lets his freak tongue flap.

Beneath the surface of Lethem’s novel, there is real pathos. Lionel Essrog and the others who Minna rescued from the boys’ home only ever had one father between them, and when he was murdered, they had nothing. They were back to where they started, motherless. There is a terrible lack in all of them that they can’t outrun or outwit, and it drives some of them to extraordinary and excessive ends.

The long gestation of Norton’s Motherless Brooklyn tells you something about why it ended up failing — it’s too afraid of failure. By making the big epic about how the evil, racist, rapist Robert Moses defiled New York, Norton has taken the easy route. Producing a morality tale calibrated to modern sensibilities, he blows the political up to a scale that leaves no room for the darkness of the human soul. Which also means that it leaves no room for comedy. The film borrows the Tourettic tics of the novel but not its brains or spine or heart. One wants to admire such an earnest effort, but it’s the earnestness that weighs the film down like a pair of cement shoes.

Jacob Siegel is the news and politics editor at Tablet magazine and the co-host of Manifesto! a Podcast.