Heroes do not become who they are in isolation. They become heroes by pushing against seemingly immovable objects that obstruct them and, of course, against other intransigent people. Our greatest political hero, President Abraham Lincoln, had to battle against Jefferson Davis and the Confederate army. Our literature’s first great epic hero, Achilles, had to confront Hector. Our greatest comic book hero, Superman, has to contend with Lex Luthor. And the character who is arguably our greatest modern movie hero, Rocky Balboa, must square off against the indomitable Apollo Creed. But unlike almost all other instances of hero formation, in the case of Rocky and Apollo Creed, the great antagonist ended up becoming a hero in his own right — and a hero who became almost as legendary as the figure he had been opposing.

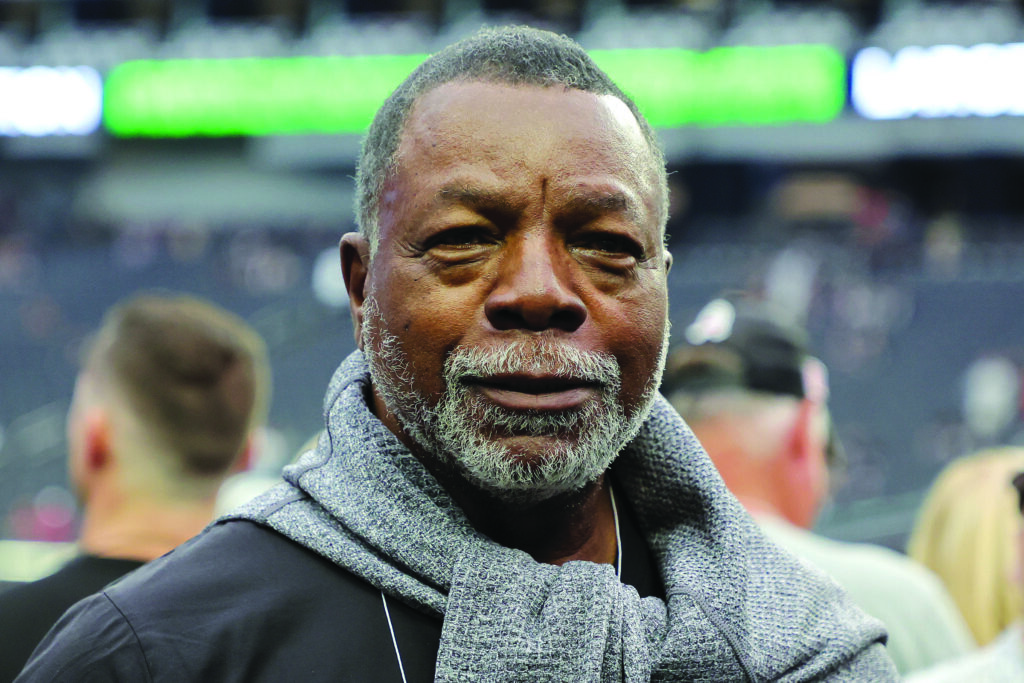

For four high-octane boxing films, Carl Weathers, who died this month at the age of 76, did not so much play Apollo Creed as incarnate him. With his sculpted, Greek-god-like frame, Lennox Lewis-like wingspan, and early-career Mike Tyson-esque aura of invincibility, Weathers’s ring presence in Rocky radiated intimidating physicality, menacing swagger, and an infectious charisma that made viewers feel as if Rocky was staring down nothing other than the second coming of Muhammad Ali. For writer and actor Sylvester Stallone, the casting of Weathers as Apollo Creed could not have been more perfect. It was Weathers’s Creed, more than anything else, that allowed Stallone’s Rocky to become a cinematic hero and, for the city of Philadelphia, an urban icon. And it was the inimitable role of Apollo Creed that allowed Weathers to go from a good if relatively unknown actor to a modern movie legend.

Weathers, who was born in New Orleans on Jan. 14, 1948, began his professional career not in acting but in sports, giving him something in common with Jim Brown, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, and other athletes who made the leap from the field (or the ring) to the screen. Weathers, who played defensive end for San Diego State University before latching on to an NFL roster as an undrafted rookie, was not as successful in his sporting career as Brown, Johnson, and Schwarzenegger were in theirs. In his one season with the Oakland Raiders (1970-71), Weathers appeared in only seven games before being cut by a coach who would later become a different sort of screen legend, John Madden. But after he pivoted to acting (his degree from San Diego State was in theater arts), it took Weathers only five years to land a role that was more indelible than any that Brown or Johnson personified. And though he never became a leading action movie star like Schwarzenegger, he did have the opportunity to act alongside him in the 1987 blockbuster Predator, impressively matching wits as well as biceps with the five-time former Mr. Universe.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Weathers’s acting career was as robust and varied as Apollo Creed’s repertoire of hooks and jabs. In addition to four Rocky films and Predator, Weathers appeared in Good Times, The Six Million Dollar Man, Arrested Development, The Shield, and Toy Story 4, and he hosted Saturday Night Live. More recently, Weathers appeared in the Star Wars spinoff series The Mandalorian, for which he earned an outstanding guest actor in a drama series Emmy nomination. My personal favorite of his non-Rocky roles is Chubbs Peterson, Adam Sandler’s sagacious (and surprisingly hilarious) golf mentor in Happy Gilmore (1996). Who could’ve guessed that the same actor who could make other boxers cry in the ring out of fear could also make audiences cry of laughter?

The aptly named Apollo Creed was a veritable hero with a thousand faces. And, like another classical hero who began his mythological career as an antagonist before becoming a hero himself — Aeneas, an archenemy of the Greeks in The Iliad who becomes the symbolic founding father of the Romans in The Aeneid — Weathers’s Apollo Creed will live on not only through his original role but through the later Creed films in which he, not Rocky, is the franchise’s founding father.

Daniel Ross Goodman is a Washington Examiner contributing writer and a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard Divinity School. His latest book, Soloveitchik’s Children: Irving Greenberg, David Hartman, Jonathan Sacks, and the Future of Jewish Theology in America, was published this summer by the University of Alabama Press.