The Real Lolita

The Kidnapping of Sally Horner and the Novel That Scandalized the World

by Sarah Weinman

Ecco, 306 pp., $27.99

In June 1948, 11-year-old Sally Horner was lured from her Camden, New Jersey home by a man named Frank La Salle, who claimed to be an FBI agent. She spent nearly two years as his captive, living in different places around the country. He told people she was his daughter. In March 1950, she used a neighbor’s phone to call home and was rescued.

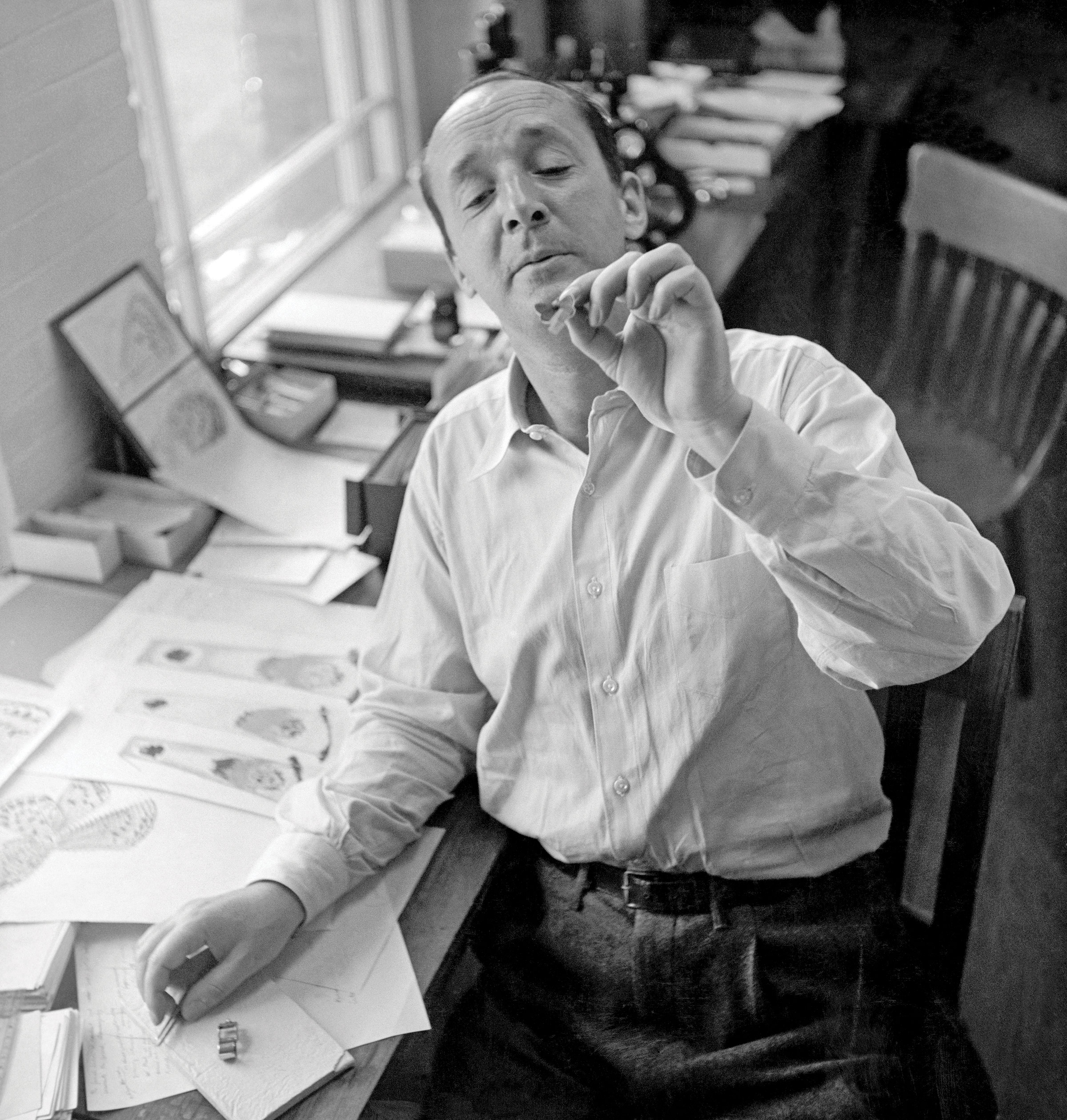

Sarah Weinman’s new book presents Sally’s plight as the “real” tale behind Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita. There are obvious similarities—the novel’s narrator, Humbert Humbert, takes 12-year-old Dolores around the country. Weinman goes down two tracks: the story of how Nabokov came to write the novel and the story of Sally’s kidnapping. We see Nabokov juggling teaching, writing, and driving around the United States to catch butterflies. At about the same time, Sally is being hauled from one part of the country to another by La Salle.

Weinman argues that Sally Horner’s fate has echoed through our culture. That seems like an overstatement—how many people have even heard her name?—but it’s true that tales of girls like her, abused and abducted, have a lurid fascination.

It’s true, too, that our culture deals awkwardly with sexuality and adolescence—a weak point that Nabokov targeted perfectly. We generally frown on grown men who leer at young women, even while companies market T-shirts saying “PORNSTAR” for children and glossy magazines encourage teen readers to experiment with sex. This cultural confusion is reflected in the law. It is possible for teenagers who have consensual sex before the age of legal consent (which varies by state from 16 to 18) to end up permanently on the sex-offender registry. Meanwhile, as New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof and activist Fraidy Reiss have exposed in recent years, child marriage is disturbingly persistent in the United States—typically between a young girl and an older man. These include cases in which the parents of a pregnant 12-year-old see marriage to her rapist as a good outcome for their daughter. So a young teen or even pre-teen girl can, depending on how her parents feel, be treated legally as a married mother-to-be or as the victim of a child rapist. Our cultural inability to draw clear lines between childhood and adulthood is part of why we find Lolita so resonant and uncomfortable.

Weinman’s retelling of Horner’s experience is heartbreaking. It is the story of a girl made vulnerable by the social expectation that children defer to adults. In her day, before the attitude of “stranger-danger” was routinely inculcated in young people, monsters like La Salle preyed on children because they could. Weinman’s meticulous research has traced where Sally was moved to by La Salle, and she does her best to imagine what Sally went through.

But what we miss is anything from Sally herself about the experience. Today we would have an interview on 60 Minutes and commentary from psychologists about her condition. Our understanding of Stockholm syndrome has changed how we think about victims who have stayed with their abductors even when there were opportunities to flee. (Public awareness of Stockholm syndrome emerged with a later and more famous kidnapping, that of Patty Hearst.) But after Sally’s rescue, she went back to a community where she was regarded as a slut. That judgmental attitude toward a young teenager who had suffered a horrific crime today seems monstrous.

Unfortunately, Weinman only gets any of this secondhand. Sally died in a car accident when she was 15. Her family is dead, too, except for a niece too young to remember her. Weinman interviews school friends, but after seven decades their memories only give us so much.

Sally Horner’s story is tragic, but her connection to Lolita is more tenuous than Weinman suggests. The idea that Nabokov was inspired specifically by this case, an argument somewhat undercut by the fact that he had been writing stories with pedophilic themes for decades, is hardly revelatory: Authors are often inspired by true crime. That he apparently denied it when asked about the Horner case—following a magazine article in the early 1960s—tells us little one way or another.

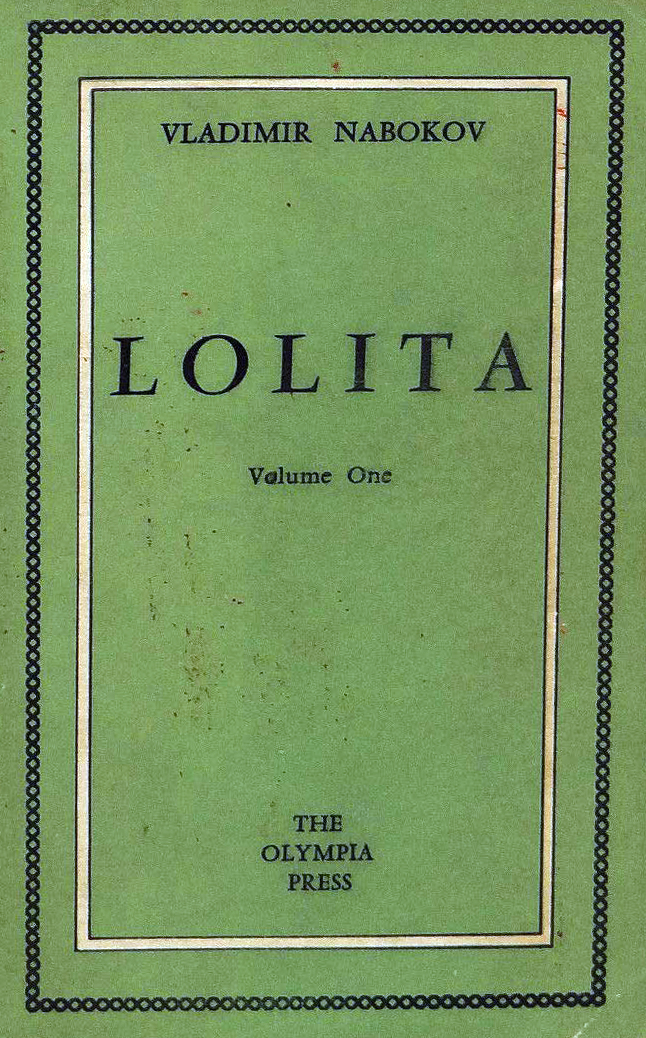

Even if Nabokov did draw on Sally’s experience, he had only slight knowledge of the basic facts. He did have a notecard—he wrote everything on notecards—on which he had jotted down some details from a newspaper account. But the case wasn’t widely covered in the press (Sally’s rescue, Weinman acknowledges, wasn’t even reported in the New York Times), so it’s hard to see how it could have been a major inspiration.

Nabokov does explicitly mention Sally Horner’s case in an aside toward the end of the novel. At that moment, Humbert Humbert is considering whether he was no different from predators like La Salle. In a sense he is posing the question to readers, who have been led to see him somewhat sympathetically.

Lolita’s literary value is in its wit and verve—in the way Nabokov makes us forget that our narrator is a villain. Nabokov made Humbert Humbert handsome and in his late 30s, a man at whom women threw themselves. He doesn’t fit our image of a child molester (and looks nothing like Frank La Salle, to judge from the mug shots). We begin to accept Humbert’s self-justifications and hate ourselves for it. Of course, most child molesters are not suave, erudite, and handsome (any more than serial killers are opera-loving Ph.D.s engaging in cat-and-mouse games with brilliant detectives).

More interesting than whether Nabokov used Sally’s experience as some of the basis for his story is why his novel struck such a nerve. How did Lolita come to be so popular, such a subject of wide controversy, and so enduring? Nabokov’s agent told him that the publisher of the book’s 1955 first edition actually hoped Lolita would encourage a change in “social attitudes toward the kind of love described in Lolita”—that is, the publisher, who mostly published smut, not literature, hoped Nabokov’s book would make society more accepting of desires like Humbert Humbert’s. (Shades of every creepy guy who’s ever given a teenage girl a Malibu and Coke and told her that “Age is just a label” and “You’re obviously an old soul” while stroking her thigh.) In Lolita, Humbert is full of the same kind of self-justification that you find from sweaty-palmed lechers in the grimier corners of the Internet, with florid discussions on the ages at which girls reach puberty. Their defense is framed in terms of evolution and biological imperative, and anyway aren’t there countries where girls are married at 11?

The way we commodify young girls’ bodies, our social veneration of virginity—and the notion that if a child is not a virgin it’s less of a crime to rape her—all this is in the pages of Nabokov’s novel. So is the cry of pedophiles everywhere that the child somehow was the seducer. Lolita challenges the boundaries of our morality, and our fascination with sex crimes is at least as strong today as it was in the 1950s. We even have a television show devoted to them: Law & Order: Special Victims Unit, about to start its 20th season. We are intrigued; we wonder about dark impulses and taboo urges; we are horrified; we cannot look away.

To call Sally the “real” Lolita is to overstate the influence of her case on Nabokov. And it’s a claim undermined by the fact that we know so little about her: We don’t know how she felt or how she understood her experience. But she deserves to be remembered—not as a literary footnote, nor even just as the victim in a tragic case, but as one who was brave enough to escape.