In 1975, Christopher Tolkien left his fellowship at New College, Oxford, to edit his late father’s massive legendarium. The prospect was daunting. The 50-year-old medievalist found himself confronted with 70 boxes of unpublished work. Thousands of pages of notes and fragments and poems, some dating back more than six decades, were stuffed haphazardly into the boxes. Handwritten texts were hurriedly scrawled in pencil and annotated with a jumble of notes and corrections. One early story was drafted in a high school exercise book.

A large portion of the archive concerned the history of J.R.R. Tolkien’s fictional world, Middle-earth. The notes contained a broader picture of a universe only hinted at in Tolkien’s two bestselling novels, The Hobbit (1937) and The Lord of the Rings (1954-55). Tolkien had intended to bring that picture to light in a lengthy, solemn history going back to creation itself, but he died before completing a final, coherent version.

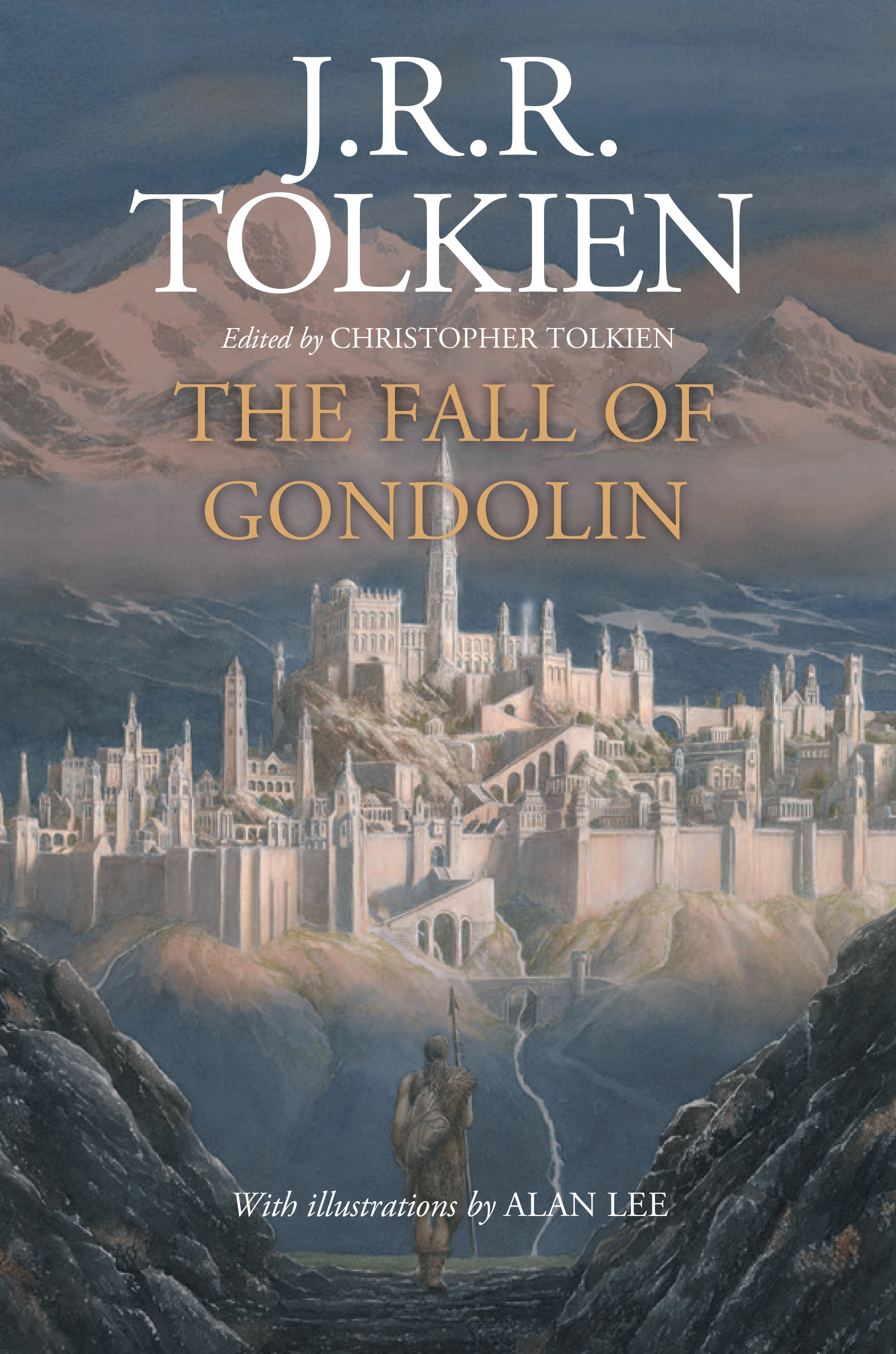

Christopher took it upon himself to edit that book, which was published in 1977 as The Silmarillion. He then turned to another project drawn from his father’s papers, then another—ultimately publishing poetry, academic works, fiction, and a 12-volume history of the creation of Middle-earth. The Fall of Gondolin, published in August, is the 25th posthumous book Christopher Tolkien has produced from his father’s archives.

Now, after more than 40 years, at the age of 94, Christopher Tolkien has laid down his editor’s pen, having completed a great labor of quiet, scholastic commitment to his father’s vision. It is the concluding public act of a gentleman and scholar, the last member of a club that became a pivotal part of 20th-century literature: the Inklings. It is the end of an era.

All of this would have come as a great surprise to 24-year-old J.R.R. Tolkien as he scrambled down the lice-ridden trenches of the Somme. Catching trench fever removed Tolkien from the front lines and probably saved his life. While on sick leave, he began a draft of The Fall of Gondolin. Now, 102 years later, it sits on the shelves of every Barnes & Noble in the country.

The first draft of The Fall of Gondolin was begun during the Great War; the final incomplete version is dated 1951. Both versions are included in the newly published book, along with fragments and working drafts. While the story itself is good, its true weight is as the final piece of the Tolkien legendarium, a project an entire century in the making.

It is work that has spanned Christopher Tolkien’s life. He started editing at just 5 years of age, catching inconsistencies in the stories his father told at bedtime. When those stories became The Hobbit, Christopher’s father promised him tuppence for every mistake he noticed in the text. A few years later, Christopher was typing up manuscripts and drawing maps of Middle-earth.

“As strange as it may seem, I grew up in the world he created,” said Christopher in a rare 2012 interview with Le Monde. “For me, the cities of The Silmarillion are more real than Babylon.”

Around the time Christopher was commissioned an officer in the RAF in 1945, Tolkien was calling his son “my chief critic and collaborator.” Christopher would return from flying missions to pore over another chapter of his father’s work. He also joined the informal literary club known as the Inklings. At 21, he was the youngest—and is now the last surviving—member. The band of friends—J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Owen Barfield, Hugo Dyson, and Charles Williams, among others—would meet at Oxford’s Eagle and Child pub or Lewis’s rooms in Magdalen College to chat about literature and philosophy and to read aloud portions of works in progress.

Christopher was recruited to narrate his father’s stories. The group considered his clear, rich voice a marked improvement over his father’s dithering, mumbling delivery. Lewis had recognized the brilliance of J.R.R. Tolkien’s work from the first moment he encountered it, and for years remained Tolkien’s only audience. Dyson, not so appreciative, exclaimed during one reading, “Oh, not another f—ing elf!”

Poet and scholar Malcolm Guite argues that the Inklings, despite their profound differences (Tolkien was an English Roman Catholic, Lewis an Ulster Protestant, Williams a hermetic mystic) refined and supported each other in their common literary mission.

“They’re not often noticed by literary historians because . . . in terms of English literature, the self-defining mainstream of 20th-century literature supposedly was high modernism, shaped by Joyce and Eliot,” Guite said in a 2011 lecture. But “there was actually . . . something quite radical going on in that group. Together, they were able to form a profoundly alternative and countercultural vision.” Guite emphasizes, in particular, the Inklings’ shared desire to respond to the materialist, largely atheistic cohort whose voices dominated the world of letters.

Although the Inklings are often accused of escapism, nearly all culture was engaged in a sort of dissociation because of the carnage and devastation of the First World War. Tolkien scholar Verlyn Flieger writes that Tolkien was “a traveler between worlds,” from his Edwardian youth to his postbellum disillusionment. It was this “oscillation that, paradoxically, makes him a modern writer, for . . . the temporal dislocation of his ‘escape’ mirrored the psychological disjunction and displacement of his century.”

High modernism found that escape in science, creating a stark divide between the material and the spiritual. This technical, technological, atomizing approach turns up in The Lord of the Rings with the villainous wizard Saruman, whose materialist philosophy dismisses the transcendent. Early in the book, Saruman changes his robe from white to multicolored. He explains, “White cloth may be dyed. The white page can be overwritten; and the white light can be broken.”

“In which case it is no longer white,” Gandalf replies. “And he that breaks a thing to find out what it is has left the path of wisdom.”

Saruman ignores that his dissection of color has eliminated something greater than the sum of its parts; he has lost view of the transcendent white light. For the Inklings, the medium of fantasy restored—or rather revealed—the enchantment of a disenchanted world. It reinstated an understanding of the transcendent that had been lost in postwar alienation.

“The value of myth,” C.S. Lewis wrote in an essay defending The Lord of the Rings, “is that it takes all the things we know and restores to them the rich significance which has been hidden by ‘the veil of familiarity.’” In this, fantasy did precisely the opposite of what its critics alleged—it did not represent a flight from the real world but a return to it, an unveiling of it. A child, Lewis wrote, “does not despise real woods because he has read of enchanted woods,” but “the reading makes all real woods a little enchanted.”

For Lewis, the revelation had greater meaning as well, since it was through his love of myths that he came to appreciate the beauty of Christianity. As a young atheist, Lewis felt the “two hemispheres of [his] mind”—reason and imagination—were irreconcilable. While he saw reason as true and “real,” imagination was beautiful but merely lies “breathed through silver.” Tolkien and Dyson rebuked this fractured thinking, explaining that Christianity reconciled the tangible fact of history with the spiritual satisfaction of myth.

“The Gospels contain a fairy-story, or a story of a larger kind which embraces all the essence of fairy-stories,” wrote Tolkien.

Lewis wrote that Tolkien and Dyson’s argument made him realize that “the story of Christ is simply a true myth: a myth working on us in the same way as the others, but with this tremendous difference that it really happened.” The Inklings saw the story of Christ as representing the perfect example of an unfragmented, undivided connection between reason and the imagination, the physical and the spiritual, the human and the divine.

Fantasy restores that undivided connection (or, to return to Tolkien’s metaphor, it unsplinters light). The genre emphasizes that the spiritual and fantastical are never far from the everyday. An ordinary hobbit like Bilbo Baggins encounters trolls just a few days’ journey from the normalcy and safety of his village. He later composes this song:

A new road or a secret gate,

And though we pass them by today,

Tomorrow we may come this way

And take the hidden paths that run

Towards the Moon or to the Sun.

This juxtaposition of the normal (a road, a gate) and the mystical (“the hidden paths that run / Towards the Moon or to the Sun”) captures perfectly Tolkien’s point: The spiritual is just around the corner. It makes you pay more attention to roads and gates in the bargain.

The everyday romance of Tolkien’s Middle-earth and Lewis’s Narnia stood in defiance of the cynical despair of the high modernists. The tension between the groups was real. When T.S. Eliot switched sides—becoming a high church Anglican, of all things!—Virginia Woolf wrote that he “may be called dead to all of us from this day forward. . . . There’s something obscene in a living person sitting by the fire and believing in God.”

The Inklings (and such of their forebears as Chesterton) sought to explain that there was nothing absurd in the secular and the sacred living cheek by jowl. In fact, it’s quite likely that one may find oneself, in Woolf’s phrase, “sitting by the fire” alongside a wizard who witnessed the singing of creation into being—as indeed Bilbo Baggins does.

This is not to say that the Inklings simply fled into a nostalgic past. They rather sought to apply its lessons to a violent and difficult present. If the Bagginses resemble throwback Victorian gentlemen and the other hobbits suggest plain English country folk of ages past, much else in The Lord of the Rings, from Saruman’s terrible machines to the mangled bodies on the Pelennor Fields, resembles the 20th century. The story ends with the Shire, which Tolkien described as “more or less a Warwickshire village of about the period of the Diamond Jubilee,” ravaged by war. Frodo, experiencing a sort of spiritual shell shock, can find no peace even when the war is long over.

The Inklings weren’t escapists. They were, Flieger writes, “a response to a response, and thus a continuation of the dialogue. . . . If the period surrounding the Great War gave birth to modernism, it also engendered the reaction against it, the effort to ensure that ‘before’ was not wholly lost in ‘after.’”

The Inklings’ efforts did not all meet the same success. Lewis’s Narnian religious allegories sold well, but his Space Trilogy was and remains underappreciated. Charles Williams wrote what Eliot called “supernatural thrillers” that have now fallen into obscurity. Tolkien, for his part, wrote the most popular high-fantasy novel of the 20th century. What accounts for the difference?

Largely, it was the way Tolkien constructed his mythology—drawing on ideas about language and creation, which he considered intimately connected. And he did nothing by halves. “His fantasy philology is just as strict as the philology of the Germanic languages that he . . . expounded as a professor,” Christopher explained in a 1996 documentary. “If he wanted a new word within one of these languages, he didn’t simply select a few syllables that attracted him. He worked out what that word would actually be and . . . the sound changes that will, fictionally, have passed over them in the course of time.”

Mythology within the mythology explained the creation of the sun and moon, the moral landscape of Middle-earth, and the origin of golf. Tales of individuals—joyful and sad—anchor the epic histories. There’s the saga of Beren, a mortal who fell in love with an elf maid, Lúthien. The voyage of Eärendil the mariner, who sailed his ship into the skies with a Silmaril upon his brow, thus becoming the brightest star in the heavens. Many of the tales concern the Silmarils—gems crafted by the firebrand warrior Fëanor—which contain the light of the trees in Valinor before they were destroyed in the dawn of the world.

“Myth-making is normally done . . . by ancient peoples whose names we don’t know,” Malcolm Guite says. “It’s just we happen to have the extraordinary example of a bloke suddenly appearing in the 20th century who became by himself the mythic equivalent of an entire people. And produced it all.”

There’s a great deal of irony that it was an uncharismatic Oxford medievalist who created the most popular adventure story of the 20th century. It’s hard to overstate his success. His inventions became clichés. Hardly any fantasy today lacks intricate made-up languages, an epic civilizational struggle against a dark power, elves and dragons and quests and powerful magical trinkets.

“Tolkien was the first,” George R.R. Martin says, “to create a fully realized secondary universe. . . . [I]n contemporary fantasy the setting becomes a character in its own right. It is Tolkien who made it so.”

The books initially attracted a following among the hippie counterculture, then surged in popularity among Catholics, then edged toward the mainstream for a couple of decades until Peter Jackson’s blockbuster films brought the stories to a massive audience. Evangelicals love them, but not for their didactic value: Christ is not present in Tolkien’s stories; there is no Aslan in The Lord of the Rings. Tolkien wished to create a story shaped by the truths he believed but without explicitly referencing them.

The reason for the broad appeal of Tolkien’s work—for its chameleonic ability to speak to every time and place and people—is that while it is full of ideas, it never becomes ideological. This approach is often a source of frustration in our explicit day (“What was Aragorn’s tax policy?” complained George R. R. Martin), but a great myth cannot lay out its answers plainly, Tolkien believed: It must do so implicitly through storytelling.

In The Lord of the Rings, the final corruption of Frodo is an inevitable and perfect solution to the facts established about his character and the ring’s corrosive power. It is also an indirect hint toward Tolkien’s belief that “the power of Evil in the world is not finally resistible by incarnate creatures.” The deus ex machina—Tolkien later confirmed it to be an actual divine intervention—that follows Frodo’s failure underlines this belief. But none of this is hinted at in the text: In-story, an exhausted hero decides to seize power for himself and a villain slips on a rock.

The Fall of Gondolin, the new book, tells the story of Tuor, a man who witnesses the demise of the last elf city to resist the terror of Morgoth. The story is written as a narrative, so it’s more accessible than the legendary history of The Silmarillion, but its fragmented and incomplete state will make it a challenge for all but the most dedicated readers.

The story itself is compelling: It is an epic, elegiac tale of Gondolin, a good but apathetic kingdom sliding into corruption and complacency. Tuor, sent on a mission by the gods, urges the city to shake off its sloth and abandon its enchanted concealment, but his warnings fall on deaf ears. The fall of Gondolin is inevitable. Yet even as the city crumbles before the fiery whips of Morgoth’s army, a child who represents hope for his people is smuggled out of its walls. Hope emerges from the darkest moment of the First Age. Alas, the 1951 version of the tale—which showcases Tolkien’s more mature, thematically complex style—remains unfinished: The story ends before Tuor even enters the gates of Gondolin.

Flipping through the crisp pages of the new book, it is impossible not to feel the weight of the legacy Christopher Tolkien has borne. He never wrote any Middle-earth stories of his own—he would hardly dare: Just editing The Silmarillion gave him a nightmare of his father’s disapproval. A few years ago, he was awarded the Bodley Medal, given by Oxford’s Bodleian Library, in recognition of his “contribution as a scholar and editor.” And now his stewardship has ended: Christopher resigned last year as director of the Tolkien Estate, and his publisher announced that Gondolin is the last book he will edit.

J.R.R. Tolkien felt anxiety about whether his work would ever be completed or published. A short story called “Leaf by Niggle” gives a glimpse. The titular character, Niggle, spends his life painting a picture of a tree, but he departs on a “journey,” leaving the picture unfinished, knowing that officials will use the canvas to patch a leaking roof.

When the discouraged Niggle finally reaches a land meant to symbolize heaven, he is distressed by his lack of accomplishment. But then he looks up.

Tolkien meant to capture the grace that grants completion and fulfillment to all of life’s wasted and half-finished undertakings. Unwittingly, he also prophesied the efforts of his youngest son. For without Christopher, we could never have beheld the sheer scope and wonder of his father’s achievement. Tolkien always saw The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion as “one long Saga of the Jewels and the Rings.” Christopher’s work, now finished, has brought the entirety of this myth, the culmination of a countercultural literary movement, a great tree “growing and bending in the wind,” into the clear, unbroken light.