When, on April 14, President Joe Biden announced the withdrawal of all remaining U.S. and foreign troops from Afghanistan, virtually no one predicted his hoped-for outcome was realistic: a negotiated settlement and power-sharing agreement between the Afghan government and the Taliban that would finally bring peace after more than 40 years of war.

But while current and former commanders, outside experts, and Republicans and Democrats alike all warned that the pullout would empower and embolden the Taliban, imperil the tenuous gains made for Afghan women, and lead to renewed civil war, few, if any, foresaw the speed at which the U.S.-trained Afghan forces would crumble, even before the last U.S. troops were gone.

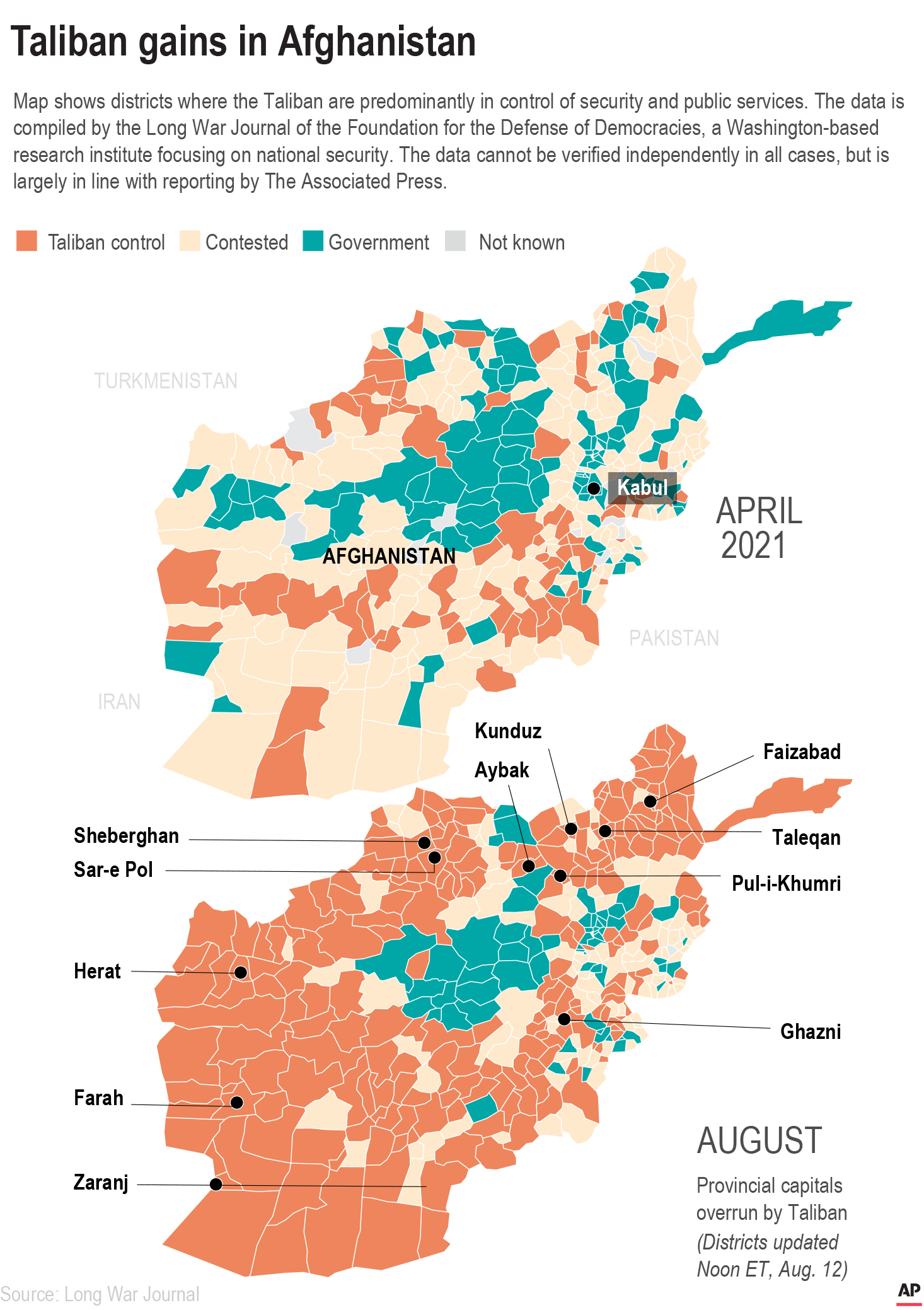

As I write this, the Taliban has seized another Afghan provincial capital, Kandahar, and by the time you read this, Kabul may well have fallen too.

“I said in the beginning that I feared that we would come to regret this decision,” said former U.S. Afghanistan commander and retired Gen. David Petraeus. “I didn’t fear that we would regret it as soon as I think we are now because this situation is seriously dire.”

The spectacle of the numerically superior and better-equipped Afghan forces, which outnumber the Taliban 300,000 to maybe 70,000, taking off their uniforms and fleeing in the face of Taliban advances is eerily reminiscent of how the ragtag Islamic State forces defeated the U.S.-trained Iraqi army in 2014 and 2015.

In 2014, Mosul fell to a lightly armed force of roughly 1,500 ISIS fighters when nearly 60,000 Iraqi soldiers and police, spooked by the brutal tactics of ISIS, just melted away.

When Ramadi fell the same way months later, Defense Secretary Ash Carter said of the Iraqi defenders, “They showed no will to fight.”

“We can give them training. We can give them equipment. We obviously can’t give them the will to fight,” he said.

The Afghan army has also shown a lack of will, and one factor may be that, as was the case in Iraq in 2015, the U.S.-backed Afghan government is rife with corruption, as documented in years of the reports from the Pentagon’s own internal watchdog.

The quarterly reports to Congress document how billions of dollars in aid, infrastructure projects, and fuel supplies have been siphoned off by corruption officials.

The 300,000 “strong” Afghan army has its ranks padded with “ghost soldiers” who are on the payroll but don’t actually show up.

And while Afghanistan’s elite commandos are considered highly capable, the grunts often suffer from fatigue, poor leadership, and low morale.

“If you don’t have fuel, the Afghan army doesn’t fight. And if they’re not being paid, they don’t fight. And if they’re not getting the bullets and the food and the other equipment, they don’t fight,” John Sopko, the special inspector general for Afghanistan reconstruction, told reporters last month. “And I think this is what you’re seeing since the Taliban started their latest attacks.”

It’s not as though the warning signs weren’t flashing red all along.

“A withdrawal … under current conditions will likely lead to a collapse of the Afghan state and a possible renewed civil war” was the conclusion of the congressionally appointed Afghanistan Study Group, headed by former Joint Chiefs Chairman and retired Marine Gen. Joseph Dunford.

“The Afghan forces are highly dependent on U.S. funding as well as operational support, and they will remain so for some time,” Dunford testified before Congress in February, adding that not only would a precipitous withdrawal risk almost-certain civil war but that within 18 to 36 months, al Qaeda and ISIS would be able to reconstitute “and present a threat to the homeland and our allies.”

In rejecting the advice of all his military commanders, Biden cited as one reason former President Donald Trump’s February 2020 agreement with the Taliban to withdraw all U.S. troops in return for a promise that American and coalition forces would not be attacked on their way out.

“It is perhaps not what I would have negotiated myself, but it was an agreement made by the United States government, and that means something,” Biden said, arguing he felt bound by what critics argued was a flawed deal.

Trump was hell-bent on getting the U.S. out of Afghanistan, which he saw as a no-win war that already had cost too many American lives (2,488) and too much money ($1.5 trillion).

With deep reservations, Trump initially went along with the Pentagon strategy of propping up the Afghan forces indefinitely until a protracted stalemate could force the Taliban to sue for peace.

“My original instinct was to pull out and, historically, I like following my instincts,” he said in an August 2017 speech. “But all my life, I’ve heard that decisions are much different when you sit behind the desk in the Oval Office.”

But Trump quickly grew impatient with the plan, eventually fired all the advisers who promoted it, and began to look for a quicker exit.

Once he signaled his strong desire to get out, the die was cast. After that, the Taliban knew they only had to wait out the Americans.

And to them, the Feb. 29 agreement amounted to total victory, tantamount to articles of surrender by the U.S.

Trump’s Pentagon chief Mark Esper tried to make the deal conditions-based by withdrawing only half the 8,000 remaining U.S. troops and then pausing to see if the Taliban met the other terms of the agreement: a requirement to reduce violence and seriously engage in peace talks.

After losing the election, Trump fired Esper and ordered the troops cut to 2,500 in an attempt to lock Biden into his plan.

Only the desperate pleas from his military commanders and key Cabinet members stopped Trump from ordering all the troops out in December.

“A conditions-based withdrawal was essentially taken off the table,” argued State Department spokesman Ned Price as the reports of the Taliban racking up victory after victory poured in.

The withdrawal was “preordained,” Price said, keeping troops in Afghanistan for another year or two or more “was never a viable option for this president.”

Biden’s Pentagon and his supporters blame the Afghan government for squandering the $83 billion the U.S. invested in building Afghanistan’s 300,000-plus armed forces, training, and equipping its own air force.

“If 300,000-plus can’t defeat 50,000 or 60,000, it’s not because 2,500 U.S. troops are gone,” said Virginia Democratic Sen. Tim Kaine on MSNBC.

The option Biden rejected was to declare the Taliban in violation of the provisions of the withdrawal agreement that required them to reduce violence and engage in real negotiations.

“I’m now the fourth United States president to preside over American troop presence in Afghanistan: two Republicans, two Democrats. I will not pass this responsibility on to a fifth,” Biden said.

Biden may say he’s only carrying out the Trump plan, but Ryan Crocker, former U.S. ambassador to Afghanistan in the Bush and Obama administrations, said Biden has made Trump’s policy his own

“He owns it,” Crocker said on ABC. “And I think it is already an indelible stain on his presidency.”

Jamie McIntyre is the Washington Examiner’s senior writer on defense and national security. His morning newsletter, “Jamie McIntyre’s Daily on Defense,” is free and available by email subscription at dailyondefense.com.