In recent weeks, the Trump administration has given new meaning to the notion of policy uncertainty. While every individual economic policy has proponents and detractors, and many would love to regularly erase rules they dislike and amplify those they love, most everyone realizes that policy certainty and predictability can also matter.

After receiving a relatively pleasing report from Robert Mueller, which eliminated a major piece of policy uncertainty, the administration threw things into flux by calling for court action to bring an end to Obamacare. With Washington abuzz, the administration said no, just kidding, and put that idea back in the policy cupboard for later development. Meanwhile, healthcare provider share values trembled.

Not many days later, the administration announced that the Mexican border will be closed tightly and immediately if Mexico fails to control the flow of drugs and asylum seekers into the United States. But then, a few days later, turning on a dime, the administration indicated that the action will be postponed for a year.

Then, if Mexico fails to control drug and people flows, the U.S. will punish American consumers by imposing 25% tariffs on Mexican-produced automobiles. In the interim, auto executives are already attempting to determine where to expand production in a new tariff-ridden world entered a new unknown into their forecasts. Their calendars are marked: Look out for March 2020.

Regime uncertainty, the inability to predict what presidents will do, is a concept associated with economic historian Robert Higgs and his exploration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s frustrated efforts to reverse the forces of the Great Depression. Higgs argues that investors, unable to predict what Roosevelt might do next with his explosion of regulatory agencies and federal programs, moved to the sidelines until the outbreak of World War II, when an all-out effort to win the war fueled new investment and ended the Great Depression.

Since Higgs’ seminal work, economists have developed systematic ways to measure economic policy uncertainty, even on a daily basis. These measurements have provided evidence that regime uncertainty punishes employment growth and economic prosperity.

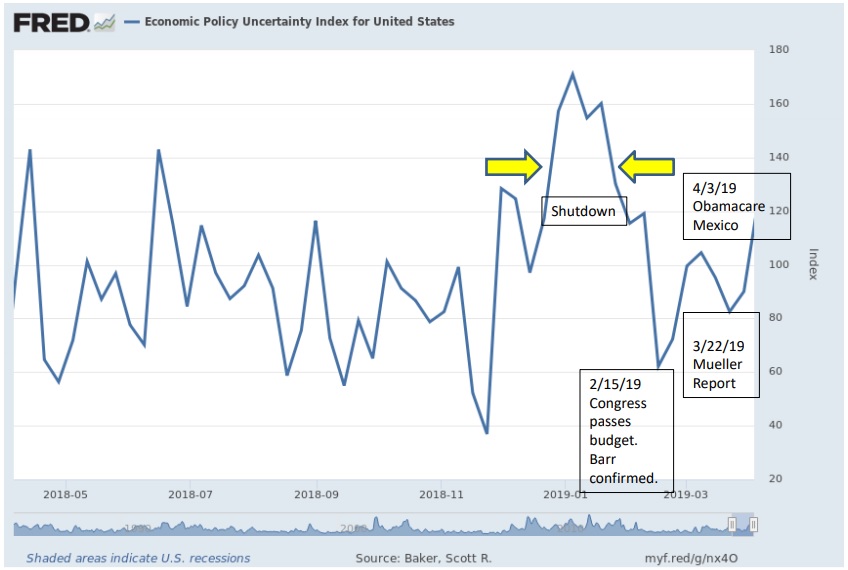

As might be expected when tracking the economy, the effects of uncertainty do not show up overnight. But high uncertainty today translates into slower times later. Just take a look at the peaks and valleys in the accompanying chart, which is based on Federal Reserve Board data giving weekly averages for economic policy uncertainty indicators.

I note the uncertainty mountain associated with the December-January government shutdown and the sharp uncertainty decline that came when Congress passed a budget that opened up the government again. The weak February employment numbers look like early indications of a slow 2019 first quarter.

I also show the reduction in uncertainty that came with the release of the Mueller report, and the offsetting uncertainty acceleration associated with the Obamacare and the Mexican border controversies.

Whether necessary or not, government action is always fraught with some uncertainty. In the process of making policy, politicians must try out ideas, send up trial balloons, and even introduce trial legislation to learn how their later actions may be improved. But the Roosevelt experience taught us that there are limits to how much policy uncertainty can be tolerated. The Trump administration, it seems, is testing those limits.

Bruce Yandle is a contributor to the Washington Examiner’s Beltway Confidential blog. He is a distinguished adjunct fellow with the Mercatus Center at George Mason University and dean emeritus of the Clemson University College of Business and Behavioral Science. He developed the “Bootleggers and Baptists” political model.