A little more than a century separates the first impeachment of a president (Andrew Johnson in 1868) from the second. (Articles of impeachment against Richard Nixon were approved by a House committee in 1974, although the president resigned before the House could impeach him.) Then, the pace accelerates: Bill Clinton (1998) was impeached 24 years later and President Trump (2019) 21 years after Clinton. Is it reasonable to assume that the interval between Trump and the next impeachment may be briefer still? Byron York’s Obsession suggests that the answer is yes.

He doesn’t say as much, but the implications seem clear: The three-year “Democratic effort to remove Trump,” writes York, “and the president’s struggle to defend himself, appear less a rushed impeachment than a long and agonizing political civil war.” Why should anyone conclude that Trump’s reelection, or for that matter a Joe Biden victory, would tame the furies that consume American politics? Impeachment, once a rare and desperate historical weapon, seems destined to become a routine feature of the struggle for political supremacy.

It was not always so. As a practical matter, the post-Civil War impeachment of Johnson by the House of Representatives was a failure: The Senate declined to convict him, and he remained in office. The case against Nixon might have been marginally stronger, but he resigned the presidency before the Senate took up his case. Clinton and Trump were impeached by the House but, like Johnson, exonerated in the Senate. In retrospect, it seems clear that Trump’s impeachment was doomed from the start. So why, and how, did it happen?

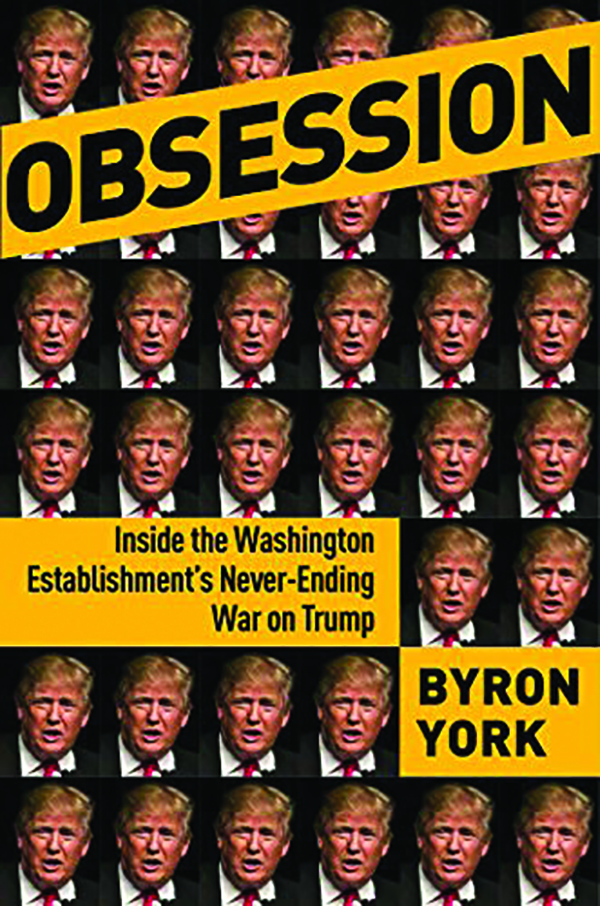

For the answer, we can be thankful for Byron York, the Washington Examiner’s chief political correspondent, a reporter of deep and varied experience, and a shrewd and judicious observer of events. Nor, it should be said, is York an entirely dispassionate chronicler: In contrast to a number of his colleagues in the press corps, he’s been around Washington for decades, and his copious, sometimes photographic memory predates the election of 2016. Accordingly, in Obsession, he is struck not so much by peripheral detail or the entertaining spectacle of Trump’s personality as by the cynical recklessness of the campaign to drive the president from office.

Politics has always been a zero-sum struggle, but as the drama of impeachment fades from memory, York’s scrupulous account cannot fail to astonish. The Democrats’ determination to impeach was already gathering force before Trump took the oath of office — indeed, before he won the election. Among other features, York offers a detailed (and mercifully compact) account of the collusion between the FBI and the Democratic National Committee to depict Trump as a witting ally of Russia during the 2016 campaign. And his portrait of FBI Director James Comey cannot help but prompt readers to reflect on the character of Washington’s permanent political class. Comey lied in public and privately to Trump, subverted his superiors in the Justice Department, and leaked self-protective memos explicitly designed to force the appointment of a special counsel.

Comey’s mishandling of Hillary Clinton’s famous email problems had, paradoxically, raised the president-elect’s suspicions about the FBI director’s competence. But Trump’s advisers were divided on the wisdom of replacing Comey. As York describes it, Trump’s relative inexperience, combined with his overconfidence in his ability to make people like him, persuaded him to try to do business with Comey. That was a fatal error, and by the time he fired Comey in May 2017, it was too late. Impeachment, once a quixotic, extravagant notion, soon became the object of Democrats’ desire.

At first, of course, Democrats pinned their hopes on Robert Mueller (Comey’s immediate predecessor as FBI director), who was appointed special counsel to investigate “collusion” between the Russian government and the Trump campaign. The new president seems to have genuinely believed that accommodating Mueller would accelerate the investigation and affirm his oft-tweeted assertion that there was no collusion. But Mueller, in the time-honored fashion of his office, found power irresistible: He swiftly concluded that there had been no collusion, but, abetted by a startlingly partisan staff and cheered on by an obsessive press, dragged out his inquiry by pursuing Trump campaign associates on minor process crimes.

When Mueller’s report was finally issued in April 2019, its effective exoneration of Trump forced congressional Democrats to grasp at the next available straw. This was provided by the revelation that a National Security Council staffer had been distressed by the policy implications of a phone call between Trump and Volodymyr Zelensky, the newly elected president of Ukraine, in which Trump asked Zelensky to “look into” Biden’s role in the 2016 firing of a Ukrainian prosecutor. That staffer, Lt. Col. Alexander Vindman, relayed his concerns to an anonymous employee of the Central Intelligence Agency, who, in turn, advised the chairman of the House Intelligence Committee, Rep. Adam Schiff, that Trump was “using the power of his office to solicit interference from a foreign country in the 2020 U.S. election.”

The anonymous whistleblower’s melodramatic claim was demonstrated neither by logic nor evidence, but Chairman Schiff and Speaker Nancy Pelosi effectively used his complaint to impeach Trump as quickly as possible in a process marked by anonymous accusations, secret hearings, and deceptive leaks by Democratic staffers to the media. They were able to impeach Trump, but not without cost: Precedent was ignored, procedures were improvised, and unlike any previous presidential reckoning, no one in the House crossed party lines. The Democrats’ three-year crusade ended in farce.

Prompted by advice from a ghost of impeachments past, the Watergate felon John Dean, Pelosi sought to “leverage” any subsequent action by withholding the articles until she had approved the Senate’s plans for trial. This elicited not a frown but a smile from Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell: “I admit I’m not sure what leverage there is,” he declared, “in refraining from sending us something we do not want.”

Philip Terzian, a former writer and editor at the Weekly Standard, is the author of Architects of Power: Roosevelt, Eisenhower, and the American Century.