Congress is on the verge of scrapping No Child Left Behind 14 years after it passed and eight years after its authorization expired.

If a fragile bipartisan compromise can be held together before lawmakers and various stakeholders can pull it apart, President George W. Bush’s biggest education reform will be replaced.

The main thing holding the compromise together is that almost everyone hates No Child Left Behind. But conservative groups say the replacement doesn’t cut the federal government’s role enough, while others such as the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights says it goes too far.

The initial response from both sides has been muted, suggesting they’re not going to lobby lawmakers hard against it. Other stakeholders have expressed tentative approval. Education Secretary Arne Duncan said he was “encouraged.” Teachers unions are giving it a qualified thumbs up as well.

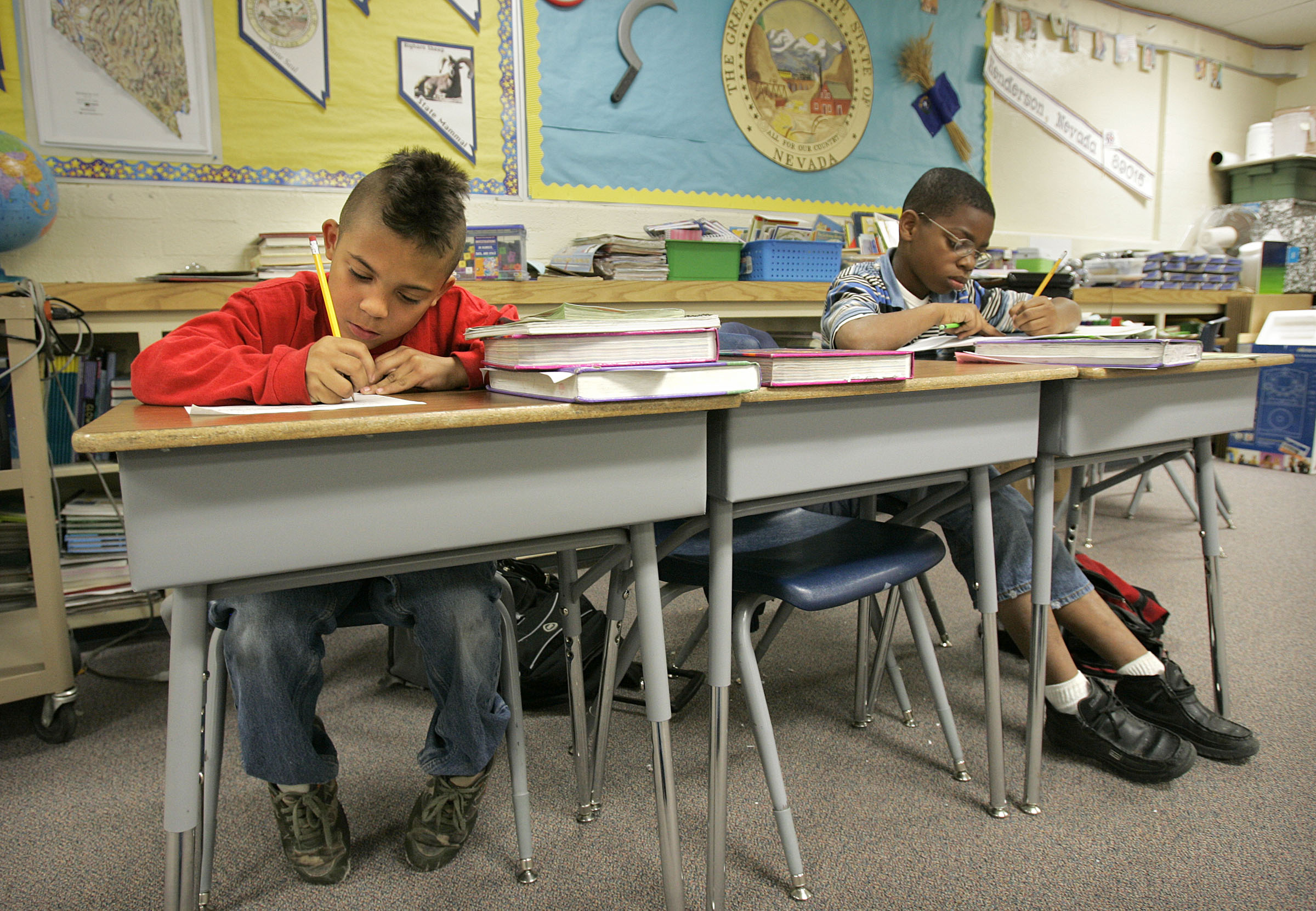

No Child Left Behind was the 2001 reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, a Civil Rights-era bill that first authorized federal funds for local projects. President George W. Bush’s version was notable for the strings attached. (AP Photo)

“We are pleased with what’s in there,” Mary Kusler, director of government relations for the National Education Association, told the Washington Examiner. “I cannot see us opposing this.”

The compromise was announced on Nov. 13, four months after the House and Senate passed their respective reauthorization bills. Less than a week later and just before Congress’ Thanksgiving recess, it was approved by a House-Senate conference. The House is now expected to vote on it in the first week of December. The Senate will follow swiftly.

That’s a breakneck pace by Congress’ standards. Sponsors want to move before momentum is lost. It helped the legislation’s chances that a fight over Syrian refugees drew most of the attention and headlines on Capitol Hill while the education bill was being completed.

Since the bill is already out of conference, it cannot be amended. So lawmakers are being given the hard sell. “[I]f I were to vote no, I would be voting to leave in place the federal Common Core mandate, the national school board and the waivers in 42 states,” said Sen. Lamar Alexander, R-Tenn., a co-author of the conference bill, during the markup.

Critics on Capitol Hill think they are getting the bum’s rush. “The fix is in,” grumbled a Republican Senate staffer who requested anonymity.

Broad agreement at first

The replacement bill for No Child Left Behind would drop the “adequate yearly progress” provisions loathed by school administrators and would give states more leeway in deciding how much tests in reading and math counted. (AP Photo)

No Child Left Behind was the name given to the 2001 reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, a Civil Rights-era bill that first authorized federal funds for local projects. Bush’s version was notable for the strings attached. To get money, schools had to meet tougher academic standards and accept rigorous testing. No Child required 100 percent of students to be proficient in math and science by the 2014-15 school year. Schools that did not show “adequate yearly progress” were labeled as deficient and faced escalating penalties for each year they did not turn things around. It also raised federal education spending by 26 percent.

While strict testing was popular at the time — No Child passed the House, 384-45, and the Senate, 91-8 — schools and teachers’ groups quickly came to despise its tough love approach, arguing the standards were draconian. Unions in particular loathe the law. A school that repeatedly misses adequate yearly progress goals can have its staff replaced and school restructured.

Neither critics nor supporters doubt teachers unions’ commitment to protecting their members; where they differ is on whether they should protect those who are evidently incompetent. Either way, American Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten has called it “insanity” to evaluate teachers based on student test scores.

Meanwhile, conservative groups found the federal government’s enhanced role in setting local education policy troubling and became receptive to complaints from school boards and local officials. By 2007, people such as Jim DeMint, who at that time was a Republican senator representing South Carolina, were calling for states to be allowed out of the act’s straitjacket. Starting in 2011, states could apply for waivers from particular provisions; 42 states have one.

“So many people are frustrated with the shackles of No Child Left Behind,” DeMint told the Washington Post in 2007. “I don’t think anyone argues with measuring what we’re doing, but the fact is, even the education community … sees us just testing, testing, testing and reshaping the curriculum so we look good.” DeMint is now president of the Heritage Foundation.

Fight over replacement

But if there was a growing consensus to replace No Child, there was no agreement about what should replace it. And some people liked No Child’s rigorous testing. Wade Henderson, president of the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, a coalition of civil rights groups, was a particular defender, arguing the law was responsible for measurable improvements for minority students.

At a February forum hosted by the American Federation of Teachers, with AFT President Randi Weingarten seated next to him, Henderson scolded No Child’s critics, saying they were making the law a scapegoat for broader problems with education. “I am not prepared to turn my back on a system that has shown some improvement,” he said. The conference has been lobbying lawmakers to preserve the accountability provisions.

There were other issues of dispute, such as funding formulas, charter schools and home schooling, on which certain lawmakers focus. Everyone, it seems, has some interest. During the reauthorization bill conference, for example, Sen. Bob Casey, D-Pa., expressed regret that the draft included no language about school bullies.

Staffers trying to arrive at a compromise bill struggled to meet everyone’s concerns. Ultimately, they watered down No Child while keeping some of its testing requirements.

The proposed replacement bill would drop the “adequate yearly progress” provisions so loathed by school administrators. States would still have to test students’ reading and math but would have leeway in how much the tests would count. Academic factors such as reading proficiency, test scores and graduation rates could account for only 50.1 percent of the school’s rating. The remainder could include subjective factors such as achievement in music and arts, and non-academic areas such as parent involvement and “school climate.” States also would be allowed to set a limit on the amount of time devoted to testing.

While strict testing was popular at the time — No Child passed the House, 384-45, and the Senate, 91-8 — schools and teachers’ groups quickly came to despise its tough love approach, arguing the standards were draconian. (AP Photo)

States would still be required to report and take action at the schools in the bottom 5 percent and ones in which a third or more of students fail to graduate. But states would be free to decide what action to take.

In short, state officials and school boards have been given wide latitude. The compromise’s architects nevertheless argued that by forcing states to address problems at the lowest-performing schools, they were retaining the intentions behind the Bush-era legislation.

“The House and Senate versions approved earlier this year did not have sufficient accountability provisions. Our version makes clear that you have to calculate and address minority student performance,” Rep. Bobby Scott, D-Va., told the Washington Examiner.

Lauren Aronson, spokeswoman for co-author Rep. John Kline, R-Minn., argued that the replacement “embodies the principles conservatives have long championed: reducing the federal role, restoring local control and empowering parents. While members found agreement on the specifics, they held firm on these core principles and these principles are reflected in the conference agreement.”

The original architects of No Child Left Behind were nevertheless dismayed. “It’s pretty meager … Forty-nine percent of a school’s rating can be based on something as loosey-goosey as ‘school climate.’ That’s not accountability,” said Sandy Kress, Bush’s education policy adviser.

What it would do

The proposal includes language stating that the education secretary and other federal officials may not “mandate, direct or control a state, local educational agency or school’s specific instructional content” and specifically mentions Common Core as part this prohibition. The language is meant to assuage conservatives’ concerns that the program, a multi-state project to create common academic standards, would be used to assert federal control over local schools.

Conservatives don’t like it much though, arguing it doesn’t go far enough to limit the federal government’s role. Heritage Foundation fellow Lindsay Burke notes that the Common Core prohibition is beside the point because the project is being done at a state level. Preventing the feds from pushing it doesn’t affect the states that have already adopted it or prevent other states from getting on board. She also said the accountability reforms were “unlikely to meaningfully reduce federal intervention in education” and the legislation did nothing to reduce federal spending.

It is not clear how much the bill will cost. It sets the authorization level, but Congress’ appropriations committees set the actual level of available funds. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the earlier Senate-passed version of bill would have authorized $23.9 billion in 2016 and $124.2 billion from 2016-20, while a House-passed version would have authorized $23.3 billion in 2016 and $116.5 billion up to 2020.

The legislation would consolidate 50 programs into state block grants and add a new $250 million federal pre-school program, a priority of President Obama’s. The bill also directs the education secretary to set aside funds for charter school programs.

Some people liked No Child’s rigorous testing. Wade Henderson, president of the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, a coalition of civil rights groups, was a particular defender, arguing the law was responsible for measurable improvements for minority students. (AP Photo)

Conservatives don’t appear to be fighting the reauthorization bill though. Only one Republican in the conference committee, Sen. Rand Paul R-Ky., voted against it, and he wasn’t even there at the conference. (Sen. Lamar Alexander, R-Tenn., cast Paul’s “no” vote by proxy.) Rep. Glenn Grothman, R-Wisc., grumbled during the conference, “The only parents back home counting on us to improve schools are the ones that flunked civics. It is up to the state legislatures and school boards to improve schools, not us.” He nevertheless voted for it.

Similarly, the Leadership Conference, which announced just prior to the conference that it flew in parents and teachers from across the county to Capitol Hill to lobby for “sufficient oversight from the U.S. Department of Education,” has been silent since the conference ended. Spokesman Scott Simpson said they were still reading the bill language.

RiShawn Biddle, an education reform activist who blogs for the site Dropoutnation.com, says even conservative lawmakers, despite their rhetoric, want to keep federal money flowing to the school districts in their backyards.

Some Republicans pushed, for example, to change the formula for allocation of Title I funding, which provides financial assistance to schools with many children from poor families. They argue that the formula shortchanges rural districts. Lawmakers pushed for an amendment to allow students to transfer to better schools outside their neighborhoods while retaining their part of the funding, but it was not adopted.

“We have conservatives and Republicans in Congress who talk a good game about federalism. It plays well back to some in the base. But in practice, they want federal funding to flow freely without accountability because it’s good for the school bureaucrats in their backyards. Which is exactly what teachers’ unions they oppose also want. If congressional Republicans want federalism, then they must cut both funding and the federal law. Otherwise they need to keep accountability in place so that taxpayers and children are served well. Which is what teachers unions and school bureaucrats don’t want,” Biddle said.