Who was Arnold Schwarzenegger?

The 75-year-old last action hero seems to be asking himself that lately, and the rest of us ought to contemplate it as well. Schwarzenegger conquered his adopted country and lived the American dream as fully as anyone before him, all without so much as sanding down the corners of his Austrian accent. Which makes him a perfect candidate to answer the question that catches up even to the men who don’t slow down: Is everything enough?

BIDEN’S CLIMATE AGENDA DREAMS COLLIDE WITH MILITARY REALITIES

Schwarzenegger has spent the majority of his existence under public scrutiny, yet the essence of the man behind this carefully cultivated persona remains elusive. After more than five decades in the spotlight, he is still “Ah-nuld,” a character whose grandiosity he has been consistently honing and marketing as he pursued wealth and success in athletics, entertainment, and politics. The recently released Netflix limited docuseries Arnold devotes an hourlong episode to each of those three stages in his career.

For those familiar with Schwarzenegger’s comprehensive 2012 autobiography Total Recall, the documentary might not introduce much fresh information. That memoir, which ends with Schwarzenegger’s split from Kennedy family heiress Maria Shriver (daughter of Sargent Shriver, Peace Corps founder and vice presidential nominee for the doomed 1972 George McGovern campaign) and a discussion of the son, Joseph Baena, he fathered with the family’s housemaid, runs a suitably hefty 656 pages. Nonetheless, the documentary does provide a fresh perspective through the lens of Schwarzenegger’s own narration. His tone of voice, his manner of presenting the material, and his evident fatigue help us understand the reality of his current existence: a solitary central European man of advanced years, in good health for his age, occupying expansive, predominantly empty homes, sharing his private space with an array of pets, and driving gas-guzzling vehicles — including some of military origins, befitting his early training as a tank driver in the Austrian army.

In many ways, Schwarzenegger embodies an archetype familiar to those of us with deep central European roots. His emotional stoicism, his unyielding focus on task completion, whether it be sweeping stables, lifting weights, memorizing lines, or giving speeches, is accompanied by an unwavering belief in his life’s accomplishments. He considers the accumulation of power as a reward that, in hindsight, justified the missteps along the way, without spending much time pondering them, save for the brief yet revealing reflections offered in this documentary and his decade-old autobiography. His daily mantra is simple: Wake up and “be useful.”

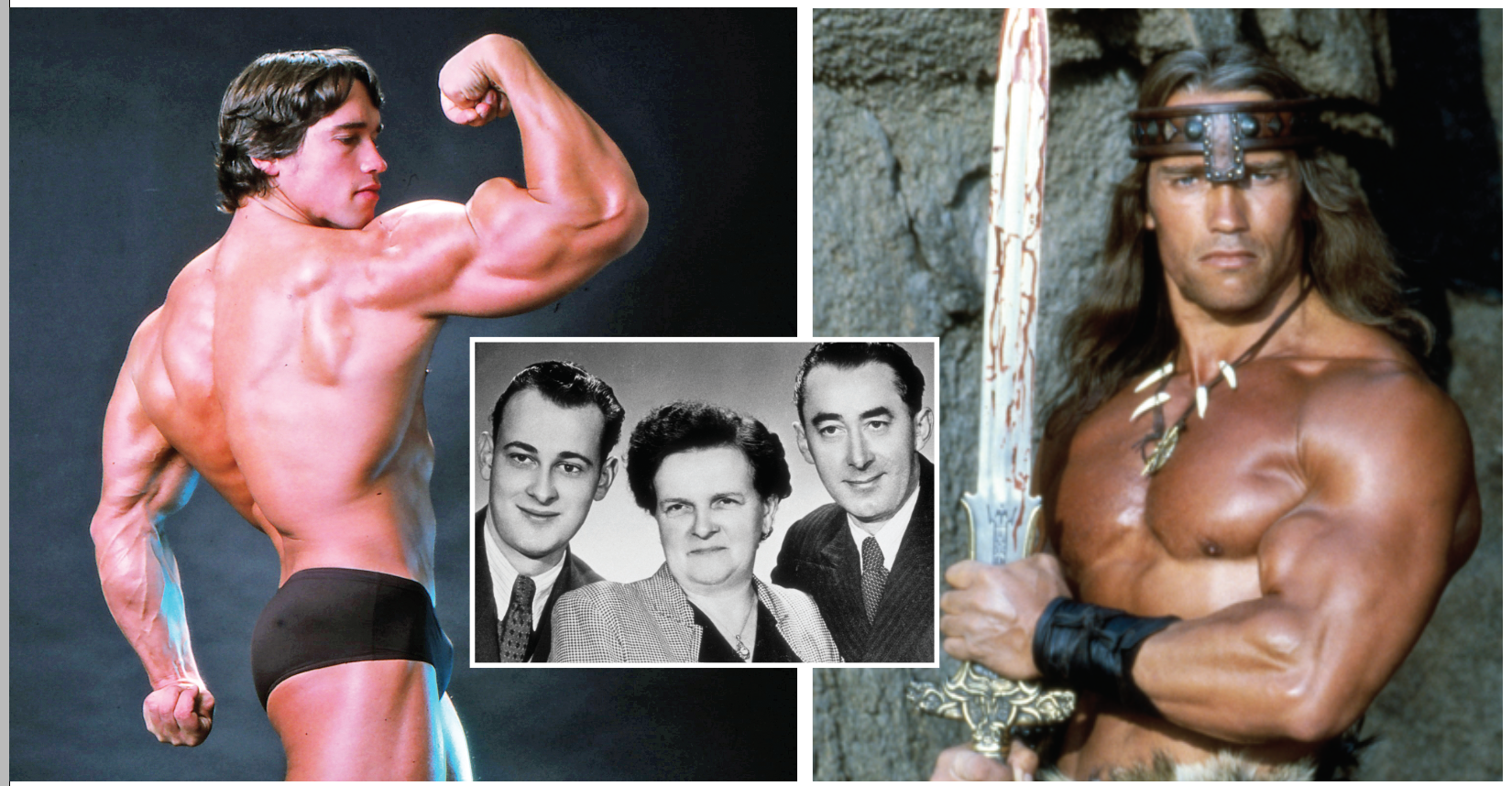

Arnold’s life story is a particularly compelling iteration of the rags-to-riches tale. Like many young Austrian men of his era, his father had fought for the armies of Nazi Germany and returned broken but functional — capable of encouraging the young Arnold and his late brother Meinhard to engage in competition and daily exercise but also a volatile alcoholic who subjected them to severe, unprovoked beatings. “Our neighbor was doing the same thing to his family, and so was the next neighbor over,” Schwarzenegger said in 2021. He grew up “surrounded by broken men.”

His mother, much like Schwarzenegger himself, was a stickler for chore completion and maintained an impeccable home. Despite his late-life solitude, Schwarzenegger’s story remains a compelling examination of one man’s ceaseless quest for success. His latest retelling of it is a highly watchable portrayal of a man who constantly reinvented himself, pushing past obstacles, to achieve the iconic status he holds today.

The meteoric rise of Schwarzenegger is inextricably linked with his discovery of muscle movies, magazines, and workouts — as Schwarzenegger himself admits, the sort of stuff that was often kept quiet, lest it occasion questions about one’s sexuality from parents and friends. As a teenager, Schwarzenegger quickly became an integral part of Austria’s burgeoning physical culture scene, participating in powerlifting, weightlifting, and bodybuilding. According to his longtime rival and multiple Mr. Olympia winner Frank Zane, this varied background enabled Schwarzenegger to develop the mass that distinguished him from his shorter, more defined competitors. It also played a pivotal role in his ultimate triumph over his toughest adversary, the Cuban weightlifter-turned-bodybuilder Sergio Oliva, who had nearly as much mass as Schwarzenegger but, as a black athlete in the 1960s and 1970s, didn’t sell as many magazine covers for Joe Weider, the Mr. Olympia creator and muscle magazine publisher. “Arnold always had size, but his definition was so-so until he began taking diet seriously,” Zane told me, an assertion that resonates in the documentary, with Schwarzenegger himself elaborating on Zane beating him in the 1968 IFBB Mr. Universe despite his comparatively small stature.

When Schwarzenegger arrived in the United States in 1968 at the age of 21, fresh from rejuvenating and thereafter dominating European bodybuilding, he breathed new life into the burgeoning American bodybuilding scene. Despite his criticism of today’s excessively bulky bodybuilders and his dismissive attitude toward steroid use, claiming it was responsible for only 5% of what he accomplished and done under a physician’s care, the physical accomplishments of his sons Patrick and Joseph Baena, both of whom have extensively trained yet fall short of matching the physique of 19-year-old Arnold, suggest there’s more complexity to this narrative. The seeming incongruity in Schwarzenegger’s actions and rhetoric, be it advocating environmental regulations while driving gas-guzzlers or touting American “liberty” while ardently endorsing government mandates, is a powerful leitmotif of his life story.

After sweeping the crowning glory of bodybuilding, the IFBB Mr. Olympia, seven times and amassing a quiet fortune through supplement sales with Weider and a real estate portfolio of rental properties, Schwarzenegger transitioned to acting. The national sensation he ignited with bodybuilding, along with his work in the 1977 bodybuilding documentary Pumping Iron, which he and director George Butler shaped into a captivating, if highly edited, narrative, and his performance as an aspiring bodybuilder in Bob Rafelson’s 1976 drama Stay Hungry, in a choice part written specifically for him by Pumping Iron author Charles Gaines, propelled him to stardom. He left bodybuilding having made it an integral part of global pop culture, but it never really stopped being the sport associated with Arnold. This mindset extended to his movie career, where his ambition wasn’t merely to become an actor but to achieve star status as “Ah-nuld.”

Throughout the 1980s, Schwarzenegger demonstrated a nuanced approach to action and comedy roles, utilizing his military background and dedication to hard work for executing myriad stunts. His distinctive Austrian accent, despite his mastery of English by the mid-1980s, became a memorable feature that added marketing value to his performances. The success of his movies, notably Conan the Barbarian, Predator, The Terminator, The Running Man, and Total Recall, owes much to directors such as John Milius, James Cameron, John McTiernan, and Paul Verhoeven. Schwarzenegger contributed the physique and arrived on set meticulously prepared for every shoot, spurred on by a rivalry with the relatively diminutive but more well-rounded Sylvester Stallone, to reach escalating box-office success. This encapsulates the Schwarzenegger method: Fulfill what’s required, vanquish any rivals, conquer the summit, and then move forward.

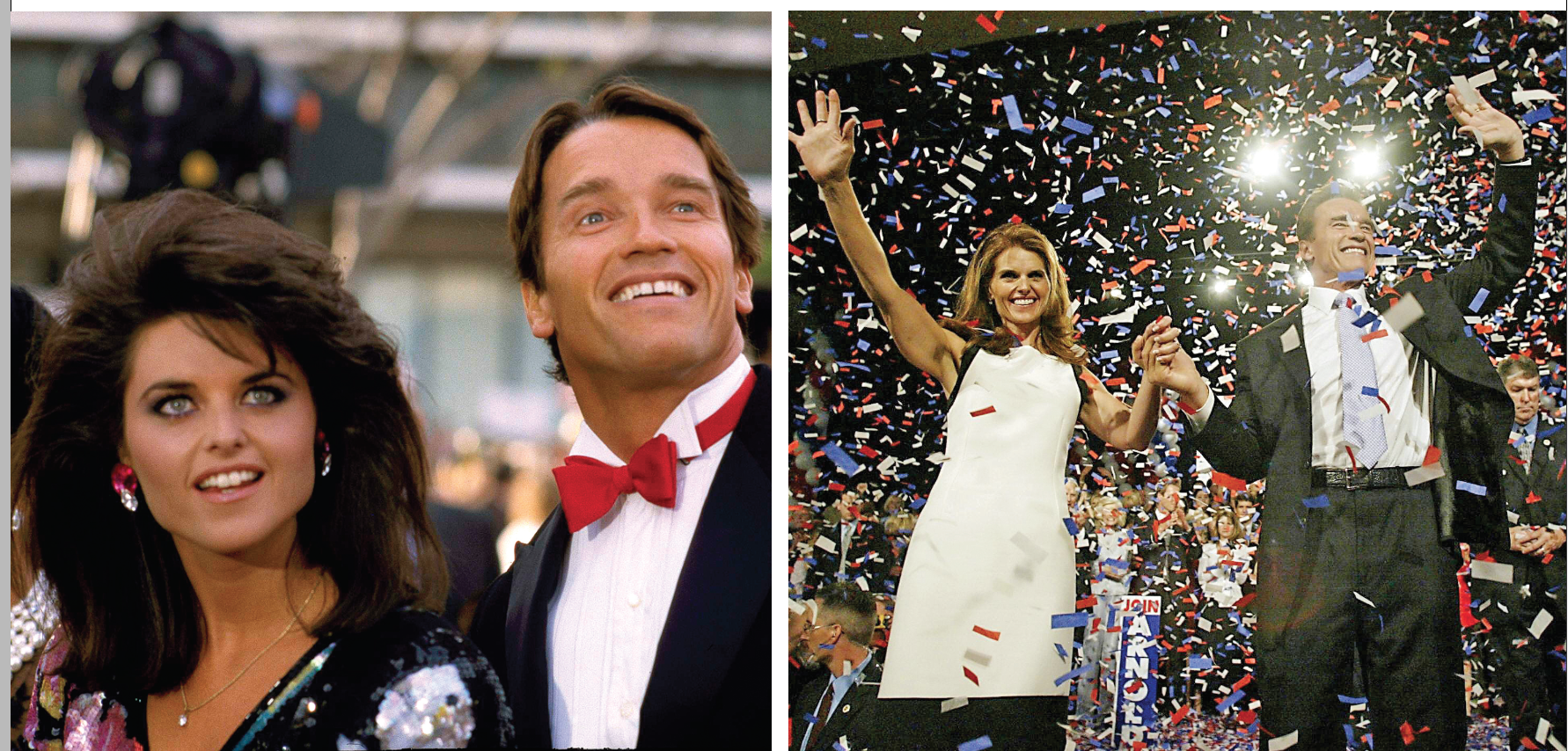

The platform for Schwarzenegger’s final act was set when he wed Maria Shriver, an accomplished journalist and a member of the formidable Kennedy clan. His acceptance by the Kennedy family gave him a leg up in terms of pursuing a political career, but he would need to pick his opportunities carefully. Recognizing the baggage he carried from a host of past sexual indiscretions, which he openly acknowledges in the documentary, Schwarzenegger, in his words, recognized the need for a European-style “short election” to secure a higher office.

When the opportunity arose in 2003 with the recall of unpopular California Gov. Gray Davis, a Democrat, the Republican-aligned Schwarzenegger seized it. The structure of the recall, comprising a yes-or-no question about the recall and another to choose a successor, was an ideal springboard for a renowned yet politically untried entity like Schwarzenegger. Despite a late-breaking scandal involving several women he had inappropriately touched, Schwarzenegger, who quickly if vaguely apologized for these misdeeds, managed to capture nearly half the vote against a multitude of opponents.

While the documentary sees Schwarzenegger attributing his Republican leanings to Ronald Reagan, in his autobiography, he references the 1968 presidential campaign that was unfolding when he arrived in the U.S. He felt Hubert Humphrey echoed the sentiments of big-government Austrian politicians, while Richard Nixon advocated free enterprise and tax cuts. Combined with a strong anti-communism sentiment, instilled in him by his proximity to communist Hungary during his formative years, these elements shaped Schwarzenegger’s minimalist political philosophy. The rest of it could be characterized as mere “will to power.” Schwarzenegger quotes Nietzsche approvingly in the documentary. In perhaps the most honest moment of the entire film, Schwarzenegger candidly explains how he exploited the artifice of politics: “Sometimes you make a deal behind the scenes, and then you go out and attack each other in front of the press. … It’s bulls***, right? But that’s politics.”

His governorship of California, spanning two terms, was characterized by expediency, especially after the 2005 defeat of his four proposed ballot initiatives designed to reshape state government. By his 2006 reelection campaign, Schwarzenegger had transitioned to a more centrist, possibly left-leaning stance, securing a resounding victory over opponent Phil Angelides in the biggest popularity contest of his life, winning 56% to 38.9%. This was the zenith of Schwarzenegger’s quest for power through fame, as his nonnative citizen status prevented him from aspiring to the presidency.

Schwarzenegger’s increasingly left-leaning governance elicited comments from then-San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom that Schwarzenegger was “becoming a Democrat.” He focused on committing California to ambitious carbon emissions reduction goals, a foreshadowing of his post-gubernatorial environmental policy pursuits. This narrative stands in stark contrast to his personal lifestyle as Schwarzenegger, who was instrumental in popularizing the behemoth SUV trend of the 1990s in the U.S. thanks to his personal Hummer, continues to drive such vehicles.

The documentary concludes with Schwarzenegger, in the vein of Mount Everest conqueror Edmund Hillary, proclaiming there are still more peaks to climb. Yet this isn’t the impression that lingers with me. The echo that resounds comes in stark contrast to the tranquil existence of Frank Zane, the 80-year-old bodybuilder-turned-zen devotee who shares a serene life of meditation with his equally health-conscious wife, Christine, who passes her time making jewelry with gemstones. Instead, what resonates is the profound absence of Shriver from Schwarzenegger’s life.

Throughout the documentary, Schwarzenegger often attributes his numerous victories to Shriver, a constant motivator in his relentless quests for excellence. Yet her presence is conspicuously missing from the film, much like most of Schwarzenegger’s children, save for Joseph Baena, who is featured prominently. Schwarzenegger’s tireless pursuit of success culminates not in a gratifying crescendo of accomplishments but in a solitary finale marked by melancholic introspection.

In his journey toward greatness, Schwarzenegger proudly adopted an unyielding mantra: persist, be useful, don’t overthink, advance. This stoic outlook finds its roots in his early life, marked by the tragic death of his brother Meinhard in a 1971 car crash caused by drunken driving — Meinhard’s drinking perhaps being a result of formative years spent with their alcoholic, abusive father. Schwarzenegger claims the abuse toughened him into the man he is today, remarking, “That which doesn’t kill me makes me stronger,” but debilitated Meinhard. The veracity of this, however, seems dubious.

Consider the spectacle of the titan of bodybuilding and cinema, the former governor, in the twilight of his life, alone in a barn, tending to his animals. One can’t help but wonder if the unspoken question on his lips is, “Is this it?” Did Schwarzenegger relentlessly toil and sacrifice every minute of every hour of every day for this?

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

The once-perfect body he prided himself on now, he readily confesses, is showing signs of decay. His model marriage ended in divorce. His political career, though impressive, had a built-in ceiling. Is this the reward for pursuing and living the American dream with such fierce tenacity?

Schwarzenegger’s story presents a stark lesson about the aftermath of the American dream. It’s a sobering testament to the loneliness that can accompany great success. The documentary may end with his unyielding resolve to scale more peaks, but it leaves us pondering the true cost of such relentless ambition — even, or perhaps especially, when that ambition has been fulfilled.

Oliver Bateman is a journalist, historian, and co-host of the What’s Left? podcast.